Germany: Public Investment to the Rescue of Growth

Author

This post is derived from the chapter dedicated to Germany in the OFCE forecast of April 2025.

Germany: Public Investment to the Rescue of Growth

After two years of recession, the German economy remains marked by sluggish consumption, a slowing industry, and a crisis in the construction sector. Adding to the economic crisis is political instability: following the snap federal elections on February 23, a “grand coalition” between the CDU/CSU and SPD emerged as the only viable option to form a stable government. On April 9, a 140-page coalition agreement was presented, outlining the main directions of the future government led by Friedrich Merz. In addition to tightening immigration policy and implementing fiscal and social reforms, this agreement provides for an increase in public investments, particularly in defense and infrastructure modernization.

The coalition agreement thus builds on the previous political agreement reached in early 2025 to launch a massive public investment plan in infrastructure and defense. This plan, financed outside the usual debt constraints, is expected to play a driving role in the recovery. Thanks to a strong budgetary impulse, Germany would regain growth of 1.5% in 2026. Public investment thus potentially becomes the key to Germany’s economic recovery. However, given the tense international context, marked by threats to foreign trade, and the first apparent cracks within the “grand coalition,”1 the future of German growth remains uncertain.

1 Current discussions on the coalition agreement are marked by disagreements on social and fiscal issues, particularly the minimum wage and taxation of low incomes. On the minimum wage issue, the CDU insists that any changes remain the responsibility of the independent commission, rejecting an automatic increase through legislation. This position has caused internal dissension within the SPD and criticism, particularly from the Jusos (the party’s youth wing) and the left wing.

2024: Second Consecutive Year of Recession

In 2024, gross domestic product (GDP) declined by 0.2% compared to the previous year; by the end of 2024, it was barely above the 2019 average. This poor performance can be explained by three factors: low private consumption despite dynamic real disposable income; a decline in manufacturing production, particularly due to loss of price competitiveness; and a crisis in the construction sector, with a loss of one-fifth of value added between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2024.

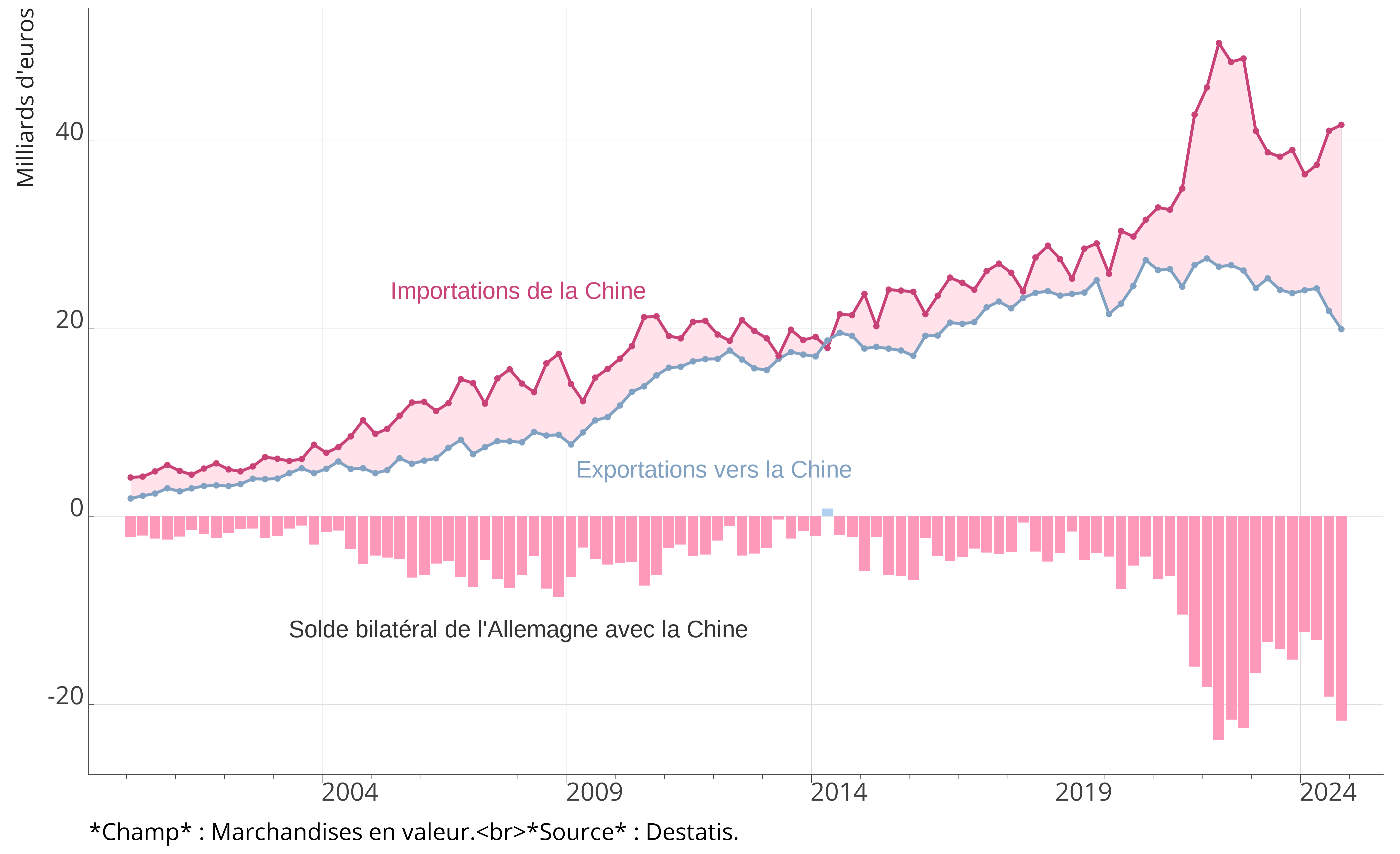

Although public consumption increased significantly (+3.5% in 2024), private household consumption expenditures remained limited, increasing by only 0.3% in 2024, despite the sustained growth in real disposable income (+1.5% in 2024), driven by dynamic real wages (+2.9%). Thus, households preferred to save due to economic uncertainty and a gloomy employment outlook marked by an increase in the unemployment rate; the savings rate increased by one point to 11.4% in 2024. In 2024, strong wage growth and weakening productivity led to a significant increase in real unit labor costs. However, this is actually a normalization, given the past declines in real wages linked to the resurgence of inflation.2 On the private investment front, gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) contracted by 2.6% in 2024, with a particularly sharp decline in investment in machinery and equipment (-5.1% in 2024). In the construction sector, GFCF also fell by 3.2% in 2024; however, the fourth quarter showed an increase, partly due to favorable weather conditions. In 2024, the contribution of foreign trade to German growth was strongly negative (-0.6 percentage points), mainly due to a decline in exports. Thus, in the fourth quarter of 2024, exports of goods and services decreased significantly (-2.2%) compared to the third quarter of 2024, despite strong global demand. This is due to the loss of competitiveness of German industry, particularly vis-à-vis China: in 2024, goods exports to China were 20% lower than their 2019 level (figure 1). Furthermore, the divergence is growing between the evolution of gross value added in volume in manufacturing and in the services sector. In the fourth quarter of 2024, the value added of manufacturing decreased by 0.6%, marking the seventh consecutive decline.

2 The level of real wages in the fourth quarter of 2024 is still 1.2% lower than its level in the fourth quarter of 2019.

A Gradual Recovery, Accelerating in 2026

The federal elections of February 23, 2025, placed the CDU-CSU at the top with 28.6% of the votes. The CDU leader, Friedrich Merz, expected to be the future chancellor, reached a preliminary agreement to form a coalition with the Social Democrats (SPD), who came in third place. This government agreement marks a major turning point for Europe’s largest economy; it notably provides for massive investment in infrastructure and defense, which should stimulate the German economy in the short term and increase long-term production potential (box 1). Thus, we anticipate a budgetary impulse of 1% of GDP in 2026, which would translate into an additional 1 percentage point of growth.

In 2025, GDP would stagnate; the weak economic environment and high levels of uncertainty would still weigh on investment, but these constraints would ease in 2026. Therefore, Germany should experience a recovery in 2026 with growth of 1.5%: in addition to a less restrictive monetary policy, it is the increase in public and private investments that would support growth. Given the significant deterioration in the productivity cycle since 2019, most of this growth would translate into productivity gains per capita, and employment would stagnate between the last quarter of 2024 and the last quarter of 2026, with a consequent increase in the unemployment rate (from 3.4% to 3.8% between 2024 and 2026). Due to the fiscal stimulus, the public deficit is expected to widen, reaching 3.1% of GDP in 2026, and public debt is expected to rise from 63.3% of GDP in 2024 to 65.2% in 2026.

Despite the budgetary stimulus, several factors will weigh on growth. Foreign trade would make a negative contribution: the increase in tariffs and the prospect of greater fragmentation of global trade will have a negative effect on German exports. Furthermore, real household disposable income is expected to stagnate in 2025 before increasing slightly in 2026. Indeed, the decline in inflation—linked in 2025 to the projected drop in energy prices—should lead to a slower increase in real wages. Although the return of growth and the decline in inflation would argue for a decrease in the savings rate—which has been durably higher compared to the pre-COVID period—it would decrease only slightly between 2024 and 2026 due to economic uncertainty and the increase in the unemployment rate. Overall, private consumption would increase by 0.4% in 2025 and 0.8% in 2026.

Special funds (Sondervermögen) are exceptional budgets created outside the ordinary federal budget, often intended to finance specific projects such as the modernization of the military or the energy transition, without directly affecting Germany’s strict debt rules. There are 29 such funds, with the oldest dating back to 1951.

Dullien, S., Jürgens, E., Paetz, C., and Watzka, S. (2021). Macroeconomic effects of a credit-financed investment program in Germany, IMK Report, 168, May 2021.

The fiscal multiplier is calculated as the weighted sum of the multipliers associated with each type of measure.

| en % |

2024

|

2025

|

de 2024t3 à 2026t4 |

2024

|

2025

|

2026

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T3 | T4 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | |||||

| PIBa | 0,1 | −0,2 | 0,1 | 0,2 | 0,2 | 0,2 | −0,2 | 0,1 | 1,5 | |

| PIB par habitanta | 0,1 | −0,2 | 0,0 | 0,2 | 0,1 | 0,2 | −0,4 | 0,1 | 1,4 | |

| Consommation ménagesa | 0,2 | 0,1 | 0,1 | 0,1 | 0,1 | 0,1 | 0,3 | 0,4 | 0,8 | |

| Consommation publiquea | 1,5 | 0,4 | −0,2 | 0,4 | 0,4 | 0,7 | 3,5 | 2,0 | 2,9 | |

| FBCF totalea,b | −0,5 | 0,4 | 0,0 | 0,4 | 0,5 | 0,6 | −2,6 | 0,3 | 4,1 | |

| dont : productive privéea | 0,1 | −0,4 | 0,2 | 0,5 | 0,6 | 0,8 | −2,3 | 0,4 | 4,2 | |

| logementa | −1,1 | 0,8 | −0,5 | 0,2 | 0,3 | 0,4 | −4,9 | −0,8 | 3,3 | |

| APUa,b | −1,6 | 2,9 | 0,3 | 0,4 | 0,4 | 0,4 | 2,7 | 1,9 | 4,7 | |

| Exportationsa,c | −1,9 | −2,2 | 0,3 | 0,2 | 0,2 | 0,2 | −1,0 | −2,0 | 1,4 | |

| Importationsa,c | 0,6 | 0,5 | 0,2 | 0,3 | 0,4 | 0,5 | 0,3 | 1,8 | 2,3 | |

| Demande intérieurea,d,e | 0,4 | 0,2 | 0,0 | 0,2 | 0,2 | 0,3 | 0,4 | 0,7 | 1,9 | |

| Variations de stocksa,e | 0,9 | 0,8 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | −0,0 | 1,1 | 0,0 | |

| Commerce extérieura,c,e | −1,1 | −1,3 | 0,0 | −0,0 | −0,1 | −0,1 | −0,6 | −1,7 | −0,4 | |

| Inflationf | 2,2 | 2,6 | 2,4 | 1,5 | 1,4 | 2,0 | 2,5 | 1,8 | 2,1 | |

| Taux de chômageg | 3,5 | 3,4 | 3,5 | 3,6 | 3,7 | 3,8 | 3,4 | 3,7 | 3,8 | |

| Solde couranth | — | — | — | — | — | — | 5,7 | 4,5 | 4,0 | |

| Déficit publich | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2,2 | 2,5 | 3,1 | |

| Dette publiqueh | — | — | — | — | — | — | 63 | 64 | 65 | |

| Impulsion budgétairei | — | — | — | — | — | — | −0,9 | 0,0 | 1,0 | |

| Sources : Destatis, prévision OFCE avril 2025. | ||||||||||

|

a En volume, aux prix chaînés. b FBCF : Formation Brute de Capital Fixe ; APU : Administrations Publiques. c Biens et services. d Demande intérieure hors variation de stocks. e Contribution à la croissance du PIB. f Evolution de l'indice des prix de consommation harmonisés (IPCH, sauf USA et France IPC). Pour les trimestres, glissement annuel (T/T(-4)) des prix. Pour les années, croissance moyenne annuelle des prix. g Au sens du BIT, en % de la population active. Pour les trimestres moyenne trimestrielle,

pour les années, moyenne annuelle. h En % du PIB annuel, en fin d'année. i Variation annuelle du déficit public (APU) primaire structurel, en points de PIB.

|

||||||||||