Reconciling funding emergencies in Europe: Defense, Climate, and Social Issues

Author

Europe must finance three priorities “at the same time.” It is possible and necessary.

European defense, which has become a priority due to the rising geopolitical tensions and the realignment of alliances under the new US administration in response to Russia’s war in Europe.

Climate and digital transition, which has been somewhat forgotten, but is essential because climate change continues, and carbon neutrality commitments must be honored. Moreover, there is a need to strengthen European public technological digital autonomy in the face of new threats posed by private digital oligarchs.

Strengthening European infrastructure and social model, in order to preserve education, healthcare, and territorial cohesion. Improving social living conditions through these investments is an essential condition for reinforcing political cohesion around humanist and progressive values in Europe. This was also the path chosen by democracies in the 1930s and in the post-war period in 1945. Failing to do so strengthens narrow nationalisms and contributes to the rise of the far-right.

It is important to emphasize the need to address these three priorities simultaneously, even if it contradicts the usual narrative: we are often told we must make “very difficult” choices between “guns” or “pensions.” Addressing all three challenges, however, is the best way—perhaps even the only way—to re-engage European citizenship—and especially its youth—by giving a true meaning and coherent values to the effort being asked of them. A sustainable, just, and peaceful future discourse will mobilize more than the fear of existential threats (which are real, let’s not deny it) hanging over Europe.

In the face of these imperatives, the budgetary capacity of each European state is limited, even though the “Rearm Europe” plan allows for relaxing the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact. A pragmatic approach, therefore, consists of diversifying and pooling financing mechanisms. These will need to explore and discuss a range of instruments that must be mobilized in the least regressive way possible (more debt, more taxes, through progressive taxation of income and wealth, carbon taxes, digital taxes, taxes on multinational companies, and possibly a bit more inflation). Let’s look at debt.

In times of urgency and war, historical studies (see here) show that substantial and quick military expenditure financing is primarily achieved through borrowing to avoid repeating the mistakes of the 1930s when England was fiscally too “prudent” to confront Nazi Germany. Thus, financing through pooled European debt (one of the options considered by the Draghi report) could benefit from the existing European framework and, in addition, develop targeted intergovernmental initiatives for risk-sharing.

Additionally, outside of military expenditure peaks (which were well known before the world wars of 1914 and 1939), there are very classic economic arguments for budgetary financing through debt: (a) public debt financing stimulates the economy during slowdowns, in periods of recession or low growth (which is the case today in Germany and France), and can finance investment expenditures without the contractionary effect of taxation; (b) debt financing of productive investments for infrastructure, education, research, or the ecological transition, can generate future growth that pays for its cost; (c) debt financing can produce more fair intergenerational distribution of efforts because certain investments (infrastructure, energy transition, but also defense and security) have long-term benefits, meaning that future generations, who will benefit from these projects, should contribute more to their financing.

Of course, the main argument against debt financing is the increase in the debt risk premium beyond a certain limit, which generally measures a borrower’s ability to repay and, therefore, their solvency. The risk of a growing debt servicing spiral (and thus the rolling over of future issues) is not negligible, but it must be compared to the risk of doing nothing in the face of these challenges or only responding partially. Moreover, there are factors that reduce this risk, like the successful experiences of controlling the term premium by Japan, other central banks’ asset purchase programs affecting long-term rates, and the capacity of more stable subscribers to reduce market volatility, supported by prudential rules (without recourse to financial repression) and/or simply moved by their own financial interest during periods of rising risks.

Indeed, additional pooled debt for Europe also comes in a new global financial context that should be leveraged to its advantage: the increasing relative risk of financial instruments in dollars and US assets, including US sovereign debt. The erratic actions of the new US administration have increased financial volatility but also potentially led to an awareness of the growing risk of US Treasuries, which were once considered the best investment in terms of risk-adjusted returns. This might result in a future shift in the composition of global bond market portfolios, which could benefit the Euro and its issuers.

For these reasons, we must not deny the importance to ensure debt sustainability, but also avoid dramatizing it, ignoring the history of emergency episodes (whether during wartime or not, like Covid-19) and the debt absorption capacity that a new impulse to european growth can provide.

Finally, the same studies also show (a) that military emergency expenditures have rarely been financed through budget cuts; and (b) that restrictive fiscal rules have always been suspended to overcome severe crises1. Insisting on immediate fiscal consolidation (“austerity”) in 2025 would therefore be a considerable risk. Using the pretext of defense additional needs, an open option for austerity is already causing a socio-political backlash and will prevent the virtuous debt growth dynamic (investment effects) from fully playing out. It was already risky and too timid before the recent acceleration of geopolitical tensions between the US and Europe, which neglected the potential for jointly revitalizing the Franco-German macroeconomic situation to address structural growth problems. A unilateral and immediate fiscal austerity response does not take into account research research showing that many technological innovations originated from military funding, and later brought growth and productivity to civilian industries. Not opening this debate in 2025 to discuss alternative expansionary economic policies in Europe, given that financing exists, social demand is pressing, and there are cross-sectoral investment growth effects, while there is at least a striking correlation between the deterioration of public goods offering (health, education, security) and the electoral rise of the far-right in Europe, seems short-sighted and a macroeconomic mistake.

1 As in 2008, Covid-19, or now Germany with the historic vote in the Bundestag.

Financing Climate and Digital: Maximizing NextGenerationEU

The NextGenerationEU (NGEU) program, authorized by the European Commission, involves joint bond issuances guaranteed by Europe up to 750 billion euros (in loans and grants), and aims to finance projects related, among other things, to the ecological and digital transition, although it was designed in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic emergency. EU member states have issued about 543 billion euros but have only used 95 billion euros in loans so far, and 171 billion euros have been disbursed by the Commission as grants. The bonds have maturities ranging from 5 to 30 years, with average rates of 2.5% to 3.5%, depending on market conditions. This leaves an issuance space, for grants and remaining usage of about 484 billion euros.

Maximizing the use of the NGEU program is important because it has an attractive borrowing cost (NGEU bonds benefit from a collective AAA rating backed by the EU budget); there is strong investor demand; the debt holders are also European and stable (the European Central Bank, sovereign wealth funds, and pension funds); and the structured framework of the program (even though complex) has been negotiated and approved, meaning the EU can raise funds without changing treaties. The remaining balance of the program should be prioritized for: green and energy infrastructure (electric grids, hydrogen, renewable energy); digital transformation (European cloud, cybersecurity, AI); and industrial innovation (clean technologies, batteries, semiconductors).

Maximizing the NGEU for these areas, its possible extension and/or its extension in the new context of 2025, would avoid increasing fiscal pressure on states and free up other sources of financing for defense.

Financing Defense through an Intergovernmental Framework

The NGEU (NextGenerationEU) cannot be “diverted” to finance defense, as Article 41(2) of the TFEU prohibits military funding via the EU budget (unless an agreement is made to amend this framework, which would require unanimity among the 27 Member States, a politically challenging task). However, defense spending remains necessary in the long term for Europe’s credibility and autonomy, even if it is primarily for deterrence purposes.

But there is a solution: issuing intergovernmental Euro-bonds for defense, with a small group of willing countries (e.g., France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Poland) that could issue “European Defense Bonds” based on the ESM model (European Stability Mechanism), outside the EU’s budget framework. It could also be possible to repurpose existing ESM funds for this purpose.

The potential characteristics of these bonds would include an initial issuance amount of €200-300 billion (which could double the amounts already discussed by European political leaders), with maturity periods ranging from 15 to 30 years. The estimated cost could be 3.5%-4.0% (slightly higher than NGEU bonds due to the lack of a direct EU budget guarantee). This approach, which is more immediate than setting up an NGEU-type program for defense (as it doesn’t require unanimity from all 27 Member States—only the willing participants), appears feasible, as there would likely be strong demand from investors2 (the rise in geopolitical tensions would make these bonds attractive to pension and sovereign funds).

2 With every issue, the allocations are oversubscribed by 10 to 15 times, demonstrating the market appetite for each issuance.

Finally, this approach does not exclude, on the contrary, thinking about the rationalization of military spending in Europe, the European preference for equipment purchases, and the choice of a defensive military strategy with the appropriate types of weapons. Industrial fragmentation and the lack of standardization in Europe’s defense industry, which harms interoperability, should certainly be reduced. There is also the need to reduce dependence on non-European suppliers, where between 2020 and 2024, the United States accounted for 65% of defense system imports by NATO European member states.

3 This is, of course, an arbitrary choice for illustrative purposes of a “coalition” of a multi-speed Europe.

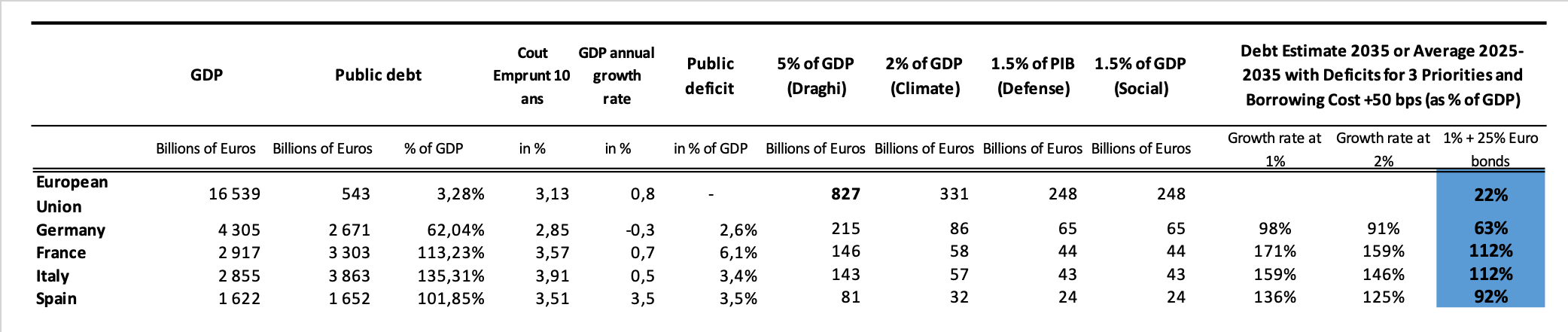

Sources: Statista, Financial Times, IMF WEO, and author’s estimates. Public debt in Euros for the European Union corresponds only to joint issuances related to the NGEU program.

Sources: Statista, Financial Times, IMF WEO, and author’s estimates. Public debt in Euros for the European Union corresponds only to joint issuances related to the NGEU program.