By Christine Rifflart

Despite the further decline in the US unemployment rate in December, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics released last week confirms paradoxically that the American labour market is in poor health. The US unemployment rate fell by 0.3 percentage point from November (-1.2 points from December 2012) to end the year at 6.7%. The rate has fallen 3.3 percentage points from a record high in October 2009, and is coming closer and closer to the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU), which since 2010 has been set by the OECD at 6.1%. However, these results do not at all reflect a rebound in employment, but instead mask a further deterioration in the economic situation.

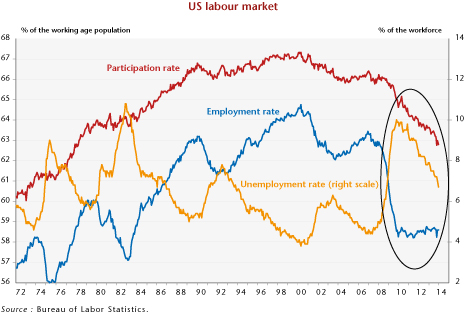

While the unemployment rate is the standard indicator for summarizing how tight a labour market is, this can also be considered using two other indicators, i.e. the employment rate and the labour force participation rate – in the US case, these give a different view of the state of the labour market (see chart).

After falling nearly 5 percentage points in 2008 and 2009, the employment rate has been constant for 4 years, at the level of the early 1980s (58.6%, following a peak of 63.4% at end 2006). Since then, the decline in the unemployment rate has reflected the decline in the participation rate, a trend that is confirmed by the figures for December. Over the period 2010-2013, the participation rate lost a little more than 2 percentage points, to wind up at end December at its lowest level since 1978 (62.8%, following a peak of 66.4% at end 2006).

This poor performance is due to insufficient job creation, which has a threefold impact. Despite positive GDP growth – which contrasts with the recession in the euro zone – demand is far from sufficient to reassure business and revitalize the labour market. After four years of recovery, at end 2013 employment has still not returned to its pre-crisis level. Net creation of salaried jobs in the private sector has not even been sufficient to absorb the demographic increase in the working age population. As a result, the employment rate is not improving from where it bottomed out.

Moreover, the difficulty in finding employment is encouraging the exit or delaying the entry or return of people who are old enough to participate in the labour market. This effect, familiar to economists, is called effet de flexion (“bending effect”) in French: young people are encouraged to study longer, women stay at home after raising their children, and unemployed people become discouraged and stop looking for work. Despite the resumption of economic growth and job creation, this effect continued to be felt in full in 2013. While the reduction in the participation rate slowed in 2011 and 2012 – the growth of the labour force was once more positive but remained lower than that of the working-age population – it accelerated in 2013 with the decline in the labour force. During the second half of 2013, 885,000 people were in effect diverted away from the labour market, due in particular to the more difficult economic and social conditions.

Companies seem reluctant to rehire in the particularly difficult economic context. The fiscal shock in early 2013 depressed activity: GDP growth fell from 2.8% in 2012 to an expected level of about 1.8% in 2013. There will be additional fiscal adjustments in 2014. Beyond drastic cuts (related to sequestration [1]) in state spending, some exceptional measures that have been in force since 2008-2009 for the poorest households and the long-term unemployed (3.9 million out of the 10.4 million unemployed) are coming to an end and have not been renewed. According to estimates by the Centre on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), 1.3 million unemployed who have exhausted their entitlement to basic benefits (26 weeks) and who have enjoyed an exceptional extension will find themselves without support as of 1 January 2014 due to the non- renewal of the measure, and nearly 5 million unemployed will be affected by the end of the year.

There is a risk of growing numbers of people falling into poverty in this situation. According to the Census Bureau, since 2010 the poverty rate has been about 15%. However, again according to the CBPP, unemployment benefits would have prevented 1.7 million people from falling below the poverty line. The greater difficulties facing the long-term unemployed and the withdrawal of part of the population from the labour market are the direct result of a morose labour market, which is not indicative of a continuous decline in the unemployment rate.

[1] See America’s fiscal headache written 9 December 2013.