By Céline Antonin, Christophe Blot, Sabine Le Bayon and Danielle Schweisguth

This text summarizes the OFCE’s 2013-2014 forecast for the euro zone economy.

After six quarters of decline, GDP in the euro zone has started to grow again in the second quarter of 2013. This upturn in activity is a positive signal that is also being corroborated by business surveys. It shows that the euro zone is no longer sinking into the depths of depression. It would nevertheless be premature to conclude that a recovery is underway, as the level of quarterly growth (0.3%) is insufficient to cause any significant reduction in unemployment. In October 2013, the unemployment rate stabilized at 12% of the workforce, a record high. Above all, the crisis is leaving scars and creating new imbalances (unemployment, job insecurity and wage deflation) that will act as obstacles to future growth, especially in certain euro zone countries.

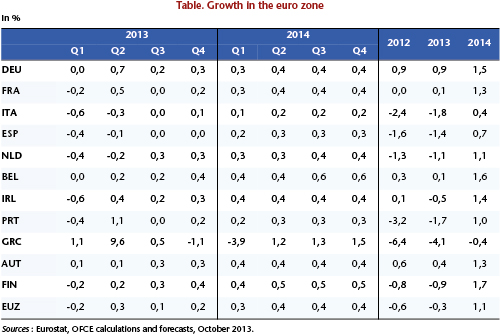

Several factors point towards a pick-up in economic activity that can be expected to continue over the coming quarters. Long-term sovereign interest rates have fallen, particularly in Spain and Italy. This reflects that the threat of a breakup of the euro zone is fading, which is due in part to the conditional support announced by the ECB a little over a year ago (see Friends of acronyms: here comes the OMT). Above all, there should be an easing of fiscal austerity, given that the European Commission has granted additional time to several countries, including France, Spain and the Netherlands, to deal with their budget deficits (see here for a summary of the recommendations made by the European Commission). Driven by the same mechanisms that we have already described in our previous forecasts, a little higher growth should follow this easing of austerity (-0.4 GDP point of fiscal effort in 2013, down from -0.9 point in 2013 and -1.8 in 2012). After two years of recession in 2012 and 2013, growth is expected to come to 1.1% in 2014.

Nevertheless, this growth will not be sufficient to erase the traces left by the widespread austerity measures implemented since 2011, which pushed the euro zone into a new recession. In particular, employment prospects are improving only very slowly because growth is too weak. Since 2008, the euro zone has destroyed 5.5 million jobs, and we do not expect a strong recovery in net job creation. Unemployment could fall in some countries, but this would be due mainly to discouraged jobseekers withdrawing from the workforce. At the same time, less austerity does not mean that there will be no austerity. With the exception of Germany, fiscal consolidation efforts will continue in all the euro zone countries. And whether this is achieved through a reduction in public spending or an increase in the tax burden, households will bear the brunt of the adjustment. At the same time, the persistence of mass unemployment will continue to fuel the deflationary pressures already at work in Spain and Greece. The improved competitiveness that results in these countries will boost exports, but at the expense of increasingly undermining domestic demand. The impoverishment of the countries of southern Europe is going to be aggravated. Growth in these countries in 2014 will again be lower than in Germany, Austria, Finland and France (Table).

As a consequence, the euro zone will be marked by increasing heterogeneity, which could wind up solidifying public opinion in different countries against the European project and making the governance of the monetary union more difficult as national interests diverge.