This text summarizes the OFCE’s October 2012 forecasts.

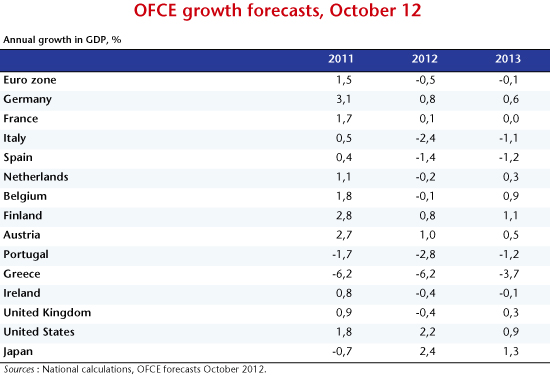

The year 2012 is ending, with hopes for an end to the crisis disappointed. After a year marked by recession, the euro zone will go through another catastrophic year in 2013 (a -0.1% decline in GDP in 2013, after -0.5% in 2012, according to our forecasts – see the table). The UK is no exception to this trend, as it plunges deeper into crisis (-0.4% in 2012, 0.3% in 2013). In addition to the figures for economic growth, unemployment trends are another reminder of the gravity of the situation. With the exception of Germany and a few other developed countries, the Western economies have been hit by high unemployment that is persisting or, in the euro zone, even rising (the unemployment rate will reach 12% in the euro zone in 2013, up from 11.2% in the second quarter of 2012). This persistent unemployment is leading to a worsening situation for those who have lost their jobs, as some fall into the ranks of the long-term unemployed and face the exhaustion of their rights to compensation. Although the United States is experiencing more favourable economic growth than in the euro zone, its labour market clearly illustrates that the US economy is mired in the Great Recession.

Was this disaster, with the euro zone at its epicentre, an unforeseeable event? Is it some fatality that we have no choice but to accept, with no alternative but to bear the consequences? No – the return to recession in fact stems from a misdiagnosis and the inability of Europe’s institutions to respond quickly to the dynamics of the crisis. This new downturn is the result of massive, exaggerated austerity policies whose impacts have been underestimated. The determination to urgently rebalance the public finances and restore the credibility of the euro zone’s economic management, regardless of the cost, has led to its opposite. To get out of this rut will require reversing Europe’s economic policy.

The difficulty posed by the current situation originates in widening public deficits and swelling public debts, which reached record levels in 2012. Keep in mind, however, that the deficits and public debts were not the cause of the crisis of 2008-2009, but its consequence. To stop the recessionary spiral of 2008-2009, governments allowed the automatic stabilizers to work; they implemented stimulus plans, took steps to rescue the financial sector and socialized part of the private debt that threatened to destabilize the entire global financial system. This is what caused the deficits. The decision to socialize the problem reflected an effort to put a stop to the freefall.

The return to recession thus grew out of the difficulty of dealing with the socialization of private debt. Indeed, in the euro zone, each country is forced to deal with financing its deficit without control of its currency. The result is immediate: a beauty contest based on who has the most rigorous public finances is taking place between the euro zone countries. Each European economic agent is, with reason, seeking the most reliable support for its assets and is finding Germany’s public debt to hold the greatest attraction. Other countries are therefore threatened in the long-term or even immediately by the drying up of their market financing. To attract capital, they must accept higher interest rates and urgently purge their public finances. But they are chasing after a sustainability that is disappearing with the recession when they seek to obtain this by means of austerity.

For countries that have control of their monetary policy, such as the United States or the United Kingdom, the situation is different. There the national savings is exposed to a currency risk if it attempts to flee to other countries. In addition, the central bank acts as the lender of last resort. Inflation could ensue, but default on the debt is unthinkable. In contrast, in the euro zone default becomes a real possibility, and the only short-term shelter is Germany, because it will be the last country to collapse. But it too will inevitably collapse if all its partners collapse.

The solution to the crisis of 2008-2009 was therefore to socialize the private debts that had become unsustainable after the speculative bubbles burst. As for what follows, the solution is then to absorb these now public debts without causing the kind of panic that we were able to contain in the summer of 2009. Two conditions are necessary. The first condition is to provide a guarantee that there will be no default on any public debt, neither partial nor complete. This guarantee can be given in the euro zone only by some form of pooling the public debt. The mechanism announced by the ECB in September 2012, the Outright Monetary Transaction (OMT), makes it possible to envisage this kind of pooling. There is, however, a possible contradiction. In effect this mechanism conditions the purchase of debt securities (and thus pooling them through the balance sheet of the ECB) on acceptance of a fiscal consolidation plan. But Spain, which needs this mechanism in order to escape the pressure of the markets, does not want to enter the OMT on just any conditions. Relief from the pressure of the markets is only worthwhile if it makes it possible to break out of the vicious circle of austerity.

The lack of preparation of Europe’s institutions for a financial crisis has been compounded by an error in understanding the way its economies function. At the heart of this error is an incorrect assessment of the value of the multipliers used to measure the impact of fiscal consolidation policies on economic activity. By underestimating the fiscal multipliers, Europe’s governments thought they could rapidly and safely re-balance their public finances through quick, violent austerity measures. Influenced by an extensive economic literature that even suggests that austerity could be a source of economic growth, they engaged in a program of unprecedented fiscal restraint.

Today, however, as is illustrated by the dramatic revisions by the IMF and the European Commission, the fiscal multipliers are much larger, since the economies are experiencing situations of prolonged involuntary unemployment. A variety of empirical evidence is converging to show this, from an analysis of the forecast errors to the calculation of the multipliers from the performances recorded in 2011 and estimated for 2012 (see the full text of our October 2012 forecast). We therefore believe that the multiplier for the euro zone as a whole in 2012 is 1.6, which is comparable to the assessments for the United States and the United Kingdom.

Thus, the second condition for the recovery of the public finances is a realistic estimate of the multiplier effect. Higher multipliers mean a greater impact of fiscal restraint on the public finances and, consequently, a lower impact on deficit reduction. It is this bad combination that is the source of the austerity-fuelled debacle that is undermining any prospect of re-balancing the public finances. Spain once again perfectly illustrates where taking this relentless logic to absurd lengths leads: an economy where a quarter of the population is unemployed, and which is now risking political and social disintegration.

But the existence of this high multiplier also shows how to break austerity’s vicious circle. Instead of trying to reduce the public deficit quickly and at any cost, what is needed is to let the economy get back to a state where the multipliers are lower and have regained their usual configuration. The point therefore is to postpone the fiscal adjustment to a time when unemployment has fallen significantly so that fiscal restraint can have the impact that it should.

Delaying the adjustment assumes that the market pressure has been contained by a central bank that provides the necessary guarantees for the public debt. It also assumes that the interest rate on the debt is as low as possible so as to ensure the participation of the stakeholders who ultimately will benefit from sustainable public finances. It also implies that in the euro zone the pooling of the sovereign debt is associated with some form of control over the long-term sustainability of the public finances of each Member State, i.e. a partial abandonment of national sovereignty that in any case has become inoperative, in favour of a supranational sovereignty which alone is able to generate the new manoeuvring room that will make it possible to end the crisis.