Céline Antonin, Christophe Blot and Danielle Schweisguth

This text summarizes the OFCE’s April 2013 forecasts

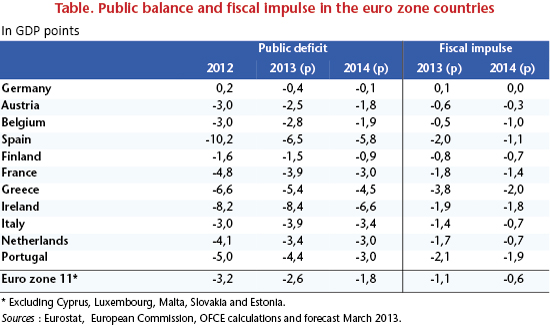

The macroeconomic and social situation in the euro zone continues to cause concern. The year 2012 was marked by a further decline in GDP (-0.5%) and a continuing rise in the unemployment rate, which reached 11.8% in December. While this new recession is not comparable in magnitude to that of 2009, it is comparable in duration, as GDP fell for the fifth consecutive time in the last quarter of 2012. Above all, for some countries (Spain, Greece and Portugal), this prolonged recession marks the beginning of deflation that could quickly spread to other countries in the euro zone (see The onset of deflation). Finally, this performance has demonstrated the failure of the macroeconomic strategy implemented in the euro zone since 2011. The strengthening of fiscal consolidation in 2012 did not restore market confidence, and interest rates did not fall except from the point when the risk of the euro zone’s collapse was mitigated by the ratification of the Treaty of stability, coordination and governance (TSCG) and the announcement of the new WTO operation allowing the ECB to intervene in the sovereign debt markets. Despite this, the fiscal dogma has not been called into question, meaning that in 2013, and if necessary in 2014, the euro zone countries will continue their forced march to reduce their budget deficits and reach the symbolic threshold of 3% as fast as possible. The incessant media refrain that France will keep its commitment is the perfect reflection of this strategy, and of its absurdity (see France: holding the required course). So until the chalice has been drunk to the dregs, the euro zone countries seem condemned to a strategy that results in recession, unemployment, social despair and the risk of political turmoil. This represents a greater threat to the sustainability of the euro zone than the lack of fiscal credibility of one or another Member State. In 2013 and 2014, the fiscal stimulus in the euro zone will again be negative (-1.1% and ‑0.6%, respectively), bringing the cumulative tightening to 4.7 GDP points since 2011. As and to the extent that countries reduce their budget deficits to less than 3%, they can slow the pace of consolidation (Table). While in the next two years Germany, which has already balanced the public books, will cease its consolidation efforts, France will have to stay the course in the hope of reaching 3% in 2014. For Spain, Portugal and Greece, the effort will be less than that what has already been done, but it will continue to be a significant burden on activity and employment, especially as the recessive impact of past measures continue to be felt.

In this context, the continuation of a recession is inevitable. GDP will fall by 0.4% in 2013. Unemployment is expected to break new records. A return to growth is not expected until 2014, but even then, in the absence of any relaxation of the fiscal dogma, hopes may again be disappointed since the anticipated growth of 0.9% will be insufficient to trigger any significant decline in unemployment. In addition, the return to growth will come too late to be able to erase the exorbitant social costs of this strategy, while alternatives to it are discussed inadequately and belatedly.