The Cour des comptes [Court of Auditors] has presented a report on the labour market which proposes that policy should be better “targeted”. With regard to unemployment benefits in particular, it focuses on the non-sustainability of expenditure and suggests certain cost-saving measures. Some of these are familiar and affect the rules on the entertainment industry and compensation for interim employees. We will not go into this here since the subject is well known [1]. But the Cour also proposes cutting unemployment benefits, which it says are (too) generous at the top and the bottom of the pay scale. In particular, it proposes reducing the maximum benefit level and establishing a digressive system, as some unemployed executives now receive benefits of over 6,000 euros per month. The reasoning in support of these proposals seems wrong on two counts.

In the first place, the diagnosis of the system’s lack of sustainability fails to take the crisis into account: if Unedic is now facing a difficult financial situation, this is above all because of falling employment and rising unemployment. It is of course natural that a social protection system designed to support employees’ income in times of crisis is running a deficit at the peak of a crisis. Seeking to rebalance Unedic’s finances today by cutting benefits would abandon the system’s countercyclical role. This would be unfair to the unemployed and economically absurd, as reducing revenues in a period of an economic downturn can only aggravate the situation. In such circumstances, it is also easy to understand that arguments for work incentives are of little value: it is at the top of the cycle, when the economy is approaching full employment, that it makes sense to raise the issue of back-to-work incentives. When the economy is bumping along the bottom, encouraging a more active job search may change the distribution of unemployment, but certainly not its level.

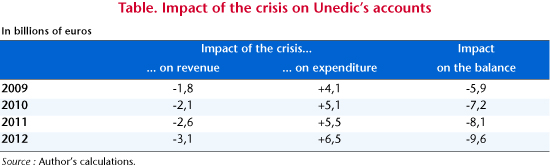

The current deficit in the unemployment insurance system simply reflects the situation of the labour market. A few calculations can help to show that the system’s generosity is fully compatible with financial stability in “normal” times. To establish this, we simply measure the impact of economic growth, employment and unemployment on the system’s deficit since 2009. In 2008, Unedic was running a financial surplus of nearly 5 billion euros [2]. This turned into a deficit of 1.2 billion euros in 2009 and 3 billion in 2010, before recovering somewhat in 2011 with a deficit of only 1.5 billion, which then rose to 2.7 billion in 2012. For 2013, the deficit is expected to reach 5 billion. The Table shows our estimates of the impact of the crisis on the system’s revenues and expenditures since 2009. The estimated revenue lost due to the crisis is based on the assumption of an increase in annual payroll of 3.5% per year (which breaks down into 2.9% for increases in the average wage and 0.6% for rises in employment) if the crisis had not occurred in 2008-2009. On the expenditure side, the estimated increase in benefits due to the crisis is based on the assumption of a stable level of “non-crisis” unemployment, with spending in this case being indexed on the trend in the average wage.

The results of this estimation clearly show that the crisis is solely responsible for the emergence of the substantial deficit run up by the unemployment insurance system. Without rising unemployment and falling employment, the system would have continued with a structural surplus, and the reform of 2009, which allowed compensation for unemployed people with shorter work references (4 months instead of 6 months), would have had only a minimal effect on its financial situation. There was no breakdown of the system, which was in fact perfectly sustainable in the long term … so long as counter-cyclical economic policies are implemented that prevent a surge in unemployment, whose sustainability is now undoubtedly more of a concern than the finances of Unedic [3].

Based on a diagnosis that is thus very questionable, the Cour des comptes has proposed reducing the generosity of unemployment benefits. Since it is difficult to put forward proposals for cutting lower benefit levels, the Cour put more emphasis on the savings that could be achieved by limiting very high benefits, which in France may exceed 6,000 euros per month for executives on high-level salaries that are up to 4 times the maximum social security cap, which in 2013 was 12,344 euros gross per month. In reality, from a strictly accounting perspective, it is not even certain that this will have positive effects on Unedic’s finances. Indeed, few people benefit from these top benefit levels, because executives are much less likely to be unemployed than are other employees. On the other hand, their higher salaries are charged at the same contribution rates, meaning that they make a net positive contribution to financing the scheme. Calculations based on the distribution of wages and of the benefits currently received by unemployed people insured by Unedic show that employees who earn more than 5,000 euros gross per month receive about 7% of unemployment benefits but provide nearly 20% of the contributions. For example, we simulated a reform that would bring French unemployment insurance into line with the German system, which is much more severely capped than the French system. The German ceiling is 5,500 euros gross per month (former Länder), against 12,344 in the French system. By retaining a cap of 5,000 euros gross per month, the maximum net benefit level in France would be around 2,800 euros. Based on this assumption, the benefits received by the unemployed in excess of the ceiling would be reduced by nearly 20%, but the savings would barely amount to more than 1% of total benefits. On the revenue side, the lower limit would result in a reduction in revenue of about 5%. The existence of a high ceiling in the French unemployment insurance system actually allows a significant vertical redistribution because of the differences in unemployment rates. Paradoxically, reducing insurance for the most privileged would lead to reducing this redistribution and undermining the system’s financial stability. Based on the above assumptions, shifting to a ceiling of 5,000 euros would increase the deficit by about 1.2 billion euros (1.6 billion revenue – 400 million expenditure).

This initial calculation does not take into account the potential impact on those whose unemployment benefits would be greatly reduced. To clarify the order of magnitude of this effect, which is, by the way, unlikely, we simulated a situation in which the number of recipients of the highest benefits would be cut in half (e.g. by a reduction in the same proportion of the time they remain unemployed). Between the new ceiling and the highest level of the reference salaries, we estimated that the incentive effect increased linearly (10% fewer unemployed in the first tranche above the ceiling, then 20% fewer, etc., up to -50%). Using this hypothesis of a high impact of benefit levels on unemployment, the additional savings on benefits would be close to 1 billion euros. In this case, the reform of the ceiling would virtually balance (with an added potential cost [not significant] of 200 million euros). But we did not include the fact that the shortening of the duration of unemployment compensation for unemployed people on high benefits could increase the duration of the unemployed on lower benefits. In a situation of near full employment, it is possible to consider that the rationing of employment results from the rationing of the supply of work; in the current situation of a generalized crisis, the more realistic case involves the opposite situation of a rationing of demand for labour. Achieving budget savings by cutting high benefit levels is not credible, at least if we stick to a reform that does not change the very nature of the system.

One could of course obtain a more favourable result by reducing only the cap on benefits and not the cap on contributions. This would be very destabilizing for the system, since it would strongly encourage executives to try to pull out of a unified solidarity system that provides them with reasonable assurances today through the acceptance of a high level of vertical redistribution, while lowering the cap on benefits alone would force them to insure themselves individually while continuing to pay high mandatory fees. This type of change would inevitably call into question the basic principle of social insurance: contributions based on each person’s means in return for benefits based on need.

The general economics in the Cour’s report on unemployment benefits thus seem highly questionable because, by not taking into account the effect of the crisis, it winds up proposing a pro-cyclical policy that puts additional burdens on the unemployed at a time when it is less possible than ever to make them bear the responsibility for underemployment. As for the key measure that challenges the compromise on high level benefits, it would at best be budget neutral and at worst destroy the social contract that today makes possible strong vertical redistribution within the unemployment insurance system.

[1] Unemployment insurance has a special scheme for interim workers in the entertainment industry worth a billion euros per year. It would obviously be sensible for this expenditure to be borne by the general budget and not by Unedic.

[2] Excluding exceptional operations.

[3] On economic policy in Europe and the lack of macroeconomic sustainability, see the initial report of the Independent Annual Growth Survey project (IAGS) .