By Jérôme Creel

In its communication of 9 November 2022, the European Commission outlined the contours of the new European fiscal framework that should, in its words, be simplified and adapted to Member States’ specific needs in order to ensure that they remain solvent and to allow for necessary reforms and investments. The new framework should also take better account of economic imbalances, including those relating to trade, and, finally, it should be better applied. A vast programme!

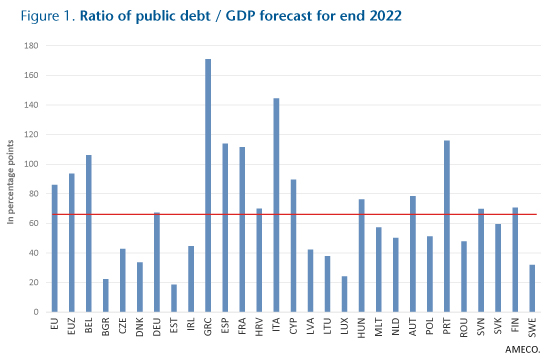

The goal of ensuring the Member States’ solvency, which is reiterated by the Commission, reflects that a significant number of Member States have excessively high public debt-to-GDP ratios within the current European fiscal framework: 12 Member States out of the 27 will have a public debt-to-GDP ratio that exceeds the 60% threshold at end 2022 (Figure 1).

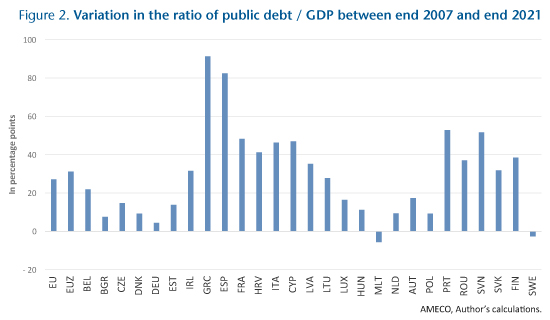

These high levels of public debt are the consequence of the series of economic, financial and geopolitical crises that have hit Europe since 2007. Between end 2007 and end 2021, public debt rose by almost 30 percentage points of GDP on average, with a dispersion of around 23 points. As Figure 2 shows, some EU Member States (recall that the Stability and Growth Pact that the Commission is planning to reform applies to all of them, not just those in the euro zone) have experienced debt increases of almost 50 points (France, Italy, Cyprus, Portugal) or even much higher (Greece, Spain). Others, like Germany, have seen their debts increase only slightly, or even decrease (Malta, Sweden). In this context, it would be difficult if not impossible to apply fiscal rules in a homogeneous or undifferentiated way, as this would require major efforts from Member States that are gradually emerging from the pandemic and are continuing to suffer from the energy crisis that is severely hurting public finances[1].

The Stability and Growth Pact, which has been in force since the creation of the euro zone in 1999, aims to ensure fiscal discipline among EU countries by preventing excessive government deficits and debts or by correcting them through fiscal policies that limit spending and boost tax revenues. As the Pact is not applied mechanically, its application depends on how the States and the Commission interpret what is meant by the “excessive” nature of deficits and debts. Although numerical criteria have been appended in a Protocol to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union – the well-known criteria of 3% of GDP for the deficit and 60% of GDP for the debt – there are exceptional circumstances that allow for temporary exemptions. So when a serious crisis occurs, as was the case in 2020 with the pandemic, the derogation clause relating to the suspension of the preventive arm of the Pact can be activated. As a result, the Pact will have been put on hold from 2020 to the end of 2023. In the Commission’s view, what should happen after that?

The Pact’s two numerical criteria would be retained, but the main tool for meeting the criteria would be changed. Fiscal sustainability[2], i.e. the reduction of public debt, would now be assessed on the basis of a single indicator: primary expenditure, i.e. public spending net of discretionary income, excluding interest charges on the debt and expenditure on unemployment benefits. The reference in the current fiscal framework to the annual reduction in the debt (one-twentieth of the difference between the current debt and the 60% of GDP target) would be dropped, as would the reference to a minimum reduction in the cyclically adjusted government deficit. The one new indicator would replace two, and hence in the Commission’s view constitute a simplification.

The primary expenditure target should ensure a plausible path for reducing the public debt towards the 60% of GDP target over 10 years. This does not imply that the debt will necessarily have reached its target after 10 years, but rather that it will be on a trend towards that at a pace deemed satisfactory.

Member States are to present the Commission with a “national medium-term fiscal and structural plan” consistent with their commitment to fiscal discipline. The primary expenditure target established in close coordination between the Member State and the Commission should therefore be consistent with the expenditure deemed necessary by both parties to ensure structural reforms and investments. The precise nature of these is not specified. The primary expenditure target could therefore differ from one country to another, in accordance with likely differences in their needs for reform and investment.

Primary expenditure in line with this fiscal discipline would be planned over a period of 3 to 4 years, engaging the State’s responsibility during this period. If unforeseen economic circumstances prevented the public debt from falling at the desired pace (the State’s commitment is accompanied by a growth scenario over the same horizon) or if the reforms and investments fail to produce the anticipated results, mainly economic growth, the adjustment in primary expenditure could be extended by up to 3 more years: the State would then have a maximum of 7 years to reduce its public debt towards the 60% of GDP target at a satisfactory pace. This would tend to greatly expand the notion of the medium term in the current version of the Stability and Growth Pact.

Since 2011, the European Union has equipped itself with instruments for monitoring macroeconomic imbalances (the overheating of wages, trade imbalances, excessive private debt, etc.), which have so far not been connected to the European fiscal framework. The Commission is proposing to integrate these into the framework. By better monitoring these imbalances, the Commission would adjust its recommendations for reforms and investments to ensure that the Member States enjoy sustainable growth and gradually reduce their debt.

Finally, the Commission is giving serious emphasis to the need for Member States to respect their commitments – the application of the Stability and Growth Pact has not always been very scrupulous – and for national bodies to more closely control these (in France, the High Council for Public Finances, the HCFP). These bodies would be responsible for organising a national debate on the relevance of the multiannual public finance assumptions made by governments.

So this is the reform project. What do we think of it?

First of all, the reform project, if adopted, would give the States greater manoeuvring room than in the current rules: reducing the debt more slowly, maintaining spending on unemployment benefits, and taking investments into account. There would be no immediate fiscal austerity.

However, adjusting primary expenditure over several years to ensure debt sustainability while taking account of the reforms and investments deemed necessary does not really seem much different from the situation prevailing today. Flexibility would be enshrined in the new draft whereas it is more a matter of improvisation in the current framework. But in practice how much does this really change? The States are by now used to modifying their fiscal policies to finance reforms and investments while ensuring their solvency. The hearings before France’s High Council on Public Finance are already supposed to stimulate the national debate on the short and medium-term orientation of public finances. On this point, too, it is rather difficult to see how the Commission’s proposal is innovative.

The a priori coherence between a potentially more flexible target for primary expenditure and the continuing need to meet the public deficit criterion is not self-evident. How much manoeuvring room will States with deficits in excess of 3% of GDP really have? They will definitely need to find new resources to reduce their deficit and maintain their primary expenditure capacity in order to finance reforms and investments. This is a major challenge, especially if macroeconomic conditionality is applied for the availability of EU funds (cohesion policy, funds from the Recovery and Resilience Facility of the Next Generation EU programme) when the public deficit is deemed excessive: the granting of EU funds may be suspended.

The major role played by the Commission in the proposed fiscal process is another significant factor. The Commission imposes the path for adjusting expenditure, and if the States fail to implement their fiscal plans and reforms on time, it may magnanimously grant them a little extra time to do so. And, in what is considered an intelligent proposal for sanctions[3], it plans to systematically require the finance ministers of countries that have not met their commitments to explain this before the European Parliament. In this fiscal process, should the role of Europe’s only democratic assembly really be limited to systematically humiliating those at fault? This provision does of course already exist, but it is not applied systematically. There are undoubtedly other ways of involving the European Parliament in the new fiscal framework.[4] But it is true that the Commission has a strong penchant for technocratic bodies, such as fiscal committees or high councils for public finance.

As for better integrating the tools for monitoring macroeconomic imbalances, the intention to ensure the overall coherence of the Commission’s recommendations is laudable. It remains to be seen however whether countries that exceed the maximum threshold for their trade surplus – which is likely to happen again once energy costs have fallen – will actually implement the recommendations. Germany’s governments have thus far never taken these into account.

Finally, there is something very mechanical in the vision of fiscal policy that this reform project conveys. Over a three- to four-year horizon, ministry officials will continue to do what they have been doing since the Stability and Growth Pact was first put into place, i.e. to calculate expenditure trajectories compatible with reducing the public debt. And, contrary to what the proposal tries to imply, the controversial notion of the output gap, i.e. the gap between unmeasurable potential GDP and actual GDP, has not disappeared from the European fiscal framework. It will remain crucial to separate the cyclically-adjusted deficit from the cyclical deficit, and the primary structural balance (the cyclically-adjusted government balance excluding interest charges) remains the benchmark for analysing debt sustainability.[5] Given the series of economic crises that we have been going through for the last 15 years and the rising debt they have generated, it is not clear that these exercises have been very useful.

[1] See the forecast for the world economy [in French] recently conducted by the OFCE’s Analysis and Forecasting Department.

[2] On the sustainability of the debt, see the special issue of the Revue d’économie financière from last month.

[3] The characterization as intelligent appears in column 3 of Figure 2 of the Commission Communication.

[4] This is the subject of my contribution to the aforementioned special issue of the Revue d’économie financière.

[5] See pp. 11-12 and p. 22 of the Commission Communication.