By Christophe Blot and Fabien Labondance

The transmission of monetary policy to economic activity and inflation takes place through various channels whose role and importance depend largely on the structural characteristics of an economy. The dynamics of credit and property prices are at the heart of this process. There are multiple sources of heterogeneity between the countries of the euro zone, which raises questions about the effectiveness of monetary policy but also about the means to be used to reduce this heterogeneity.

The possible sources of heterogeneity between countries include the degree of concentration of the banking systems (i.e. more or fewer banks, and therefore more or less competition), the financing arrangements (i.e. fixed or variable rates), the maturity of household loans, their levels of debt, the proportion of households renting, and the costs of transactions on the housing market. The share of floating rate loans perfectly reflects these heterogeneities, as it is 91% in Spain, 67% in Ireland and 15% in Germany. In these conditions, the common monetary policy of the European Central Bank (ECB) has asymmetric effects on the euro zone countries, as is evidenced by the divergences in property prices in these countries. These asymmetries will then affect GDP growth, a phenomenon that has been observed both “before” and “after” the crisis. These issues are the subject of an article that we published in the OFCE’s Ville et Logement (Housing and the City) issue. We evaluated heterogeneity in the transmission of monetary policy to property prices in the euro zone by explicitly distinguishing two steps in the transmission channel, with each step potentially reflecting different sources of heterogeneity. The first describes the impact of the interest rates controlled by the ECB on the rates charged for property loans by the banks in each euro zone country. The second step involves the differentiated impact of these bank rates on property prices.

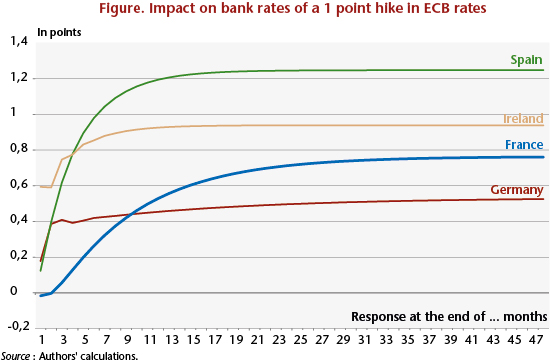

Our results confirm the existence of divergences in the transmission of monetary policy in the euro zone. Thus, for a constant interest rate set by the ECB at 2%, as was the case between 2003 and 2005, the estimates made during the period preceding the crisis suggest that the long-term equilibrium rate applied respectively by Spanish banks and Irish banks would be 3.2% and 3.3%. In comparison, the equivalent rate in Germany would be 4.3%. Moreover, the higher rates in Spain and Ireland amplify this gap in nominal rates. We then show that the impact on bank rates of changes in the ECB’s key rate is, before the crisis, stronger in Spain and Ireland than it is in Germany (figure), which is related to differences in the share of loans made at floating rates in these countries. It should be noted that the transmission of monetary policy was severely disrupted during the crisis. The banks did not necessarily adjust supply and demand for credit by changing rates, but by tightening the conditions for granting loans. [1] Furthermore, estimates of the relationship between the rates charged by banks and property prices suggest a high degree of heterogeneity within the euro zone. These various findings thus help to explain, at least partially, the divergences seen in property prices within the euro zone. The period during which the rate set by the ECB was low helped fuel the housing boom in Spain and Ireland. The tightening of monetary policy that took place after 2005 would also explain the more rapid adjustment in property prices observed in these two countries. Our estimates also suggest that property prices in these two countries are very sensitive to changes in economic and population growth. Property cycles cannot therefore be reduced to the effect of monetary policy.

To the extent that the recent crisis has its roots in the macroeconomic imbalances that developed in the euro zone, it is essential for the proper functioning of the European Union to reduce the sources of heterogeneity between the Member states. However, this is not necessarily the responsibility of monetary policy. First, it is not certain that the instrument of monetary policy, short-term interest rates, is the right tool to curb the development of financial bubbles. And second, the ECB conducts monetary policy for the euro zone as a whole by setting a single interest rate, which does not permit it to take into account the heterogeneities that characterize the Union. What is needed is to encourage the convergence of the banking and financial systems. In this respect, although the proposed banking union still raises many problems (see Maylis Avaro and Henri Sterdyniak), it may reduce heterogeneity. Another effective way to reduce asymmetry in the transmission of monetary policy is through the implementation of a centralized supervisory policy that the ECB could oversee. This would make it possible to strengthen the resilience of the financial system by adopting a means of regulating banking credit that could take into account the situation in each country in order to avoid the development of the bubbles that pose a threat to the countries and the stability of the monetary union (see CAE report no. 96 for more details).

[1] Kremp and Sevestre (2012) emphasize that the reduction in borrowing volumes is not due simply to the rationing of the supply of credit but that the recessionary context has also led to a reduction in demand.