The duration of the Greek crisis and the harshness of the series of austerity plans that have been imposed on it to straighten out its public finances and put it in a position to meet its obligations to its creditors have upset European public opinion and attracted great comment. The hard-fought agreement reached on Monday 13 July at the summit of the euro zone heads of state and government, along with the demands made prior to the Greek referendum on 5 July, which were rejected by a majority of voters, contain conditions that are so unusual and so contrary to State sovereignty as we are used to conceiving of it that they shocked many of Europe’s citizens and strengthened the arguments of eurosceptics, who see all this as proof that European governance is being exercised contrary to democracy.

By requiring that the creditors be consulted on any bill affecting the management of the public finances and by requiring that the privatizations, with their lengthy list dictated by the creditors, be managed by a fund that is independent of the Greek government, the euro zone’s leaders have in reality put Greece’s public finances under supervision. Furthermore, the measures contained in the new austerity plan are likely to further depress the already depressed domestic demand, exacerbating the recession that has racked the Greek economy in 2015, following a brief slight upturn in 2014.

Impoverishment without adjustment

The Greek crisis, which in 2010 triggered the sovereign debt crisis in the euro zone, has seen prolonged agony punctuated by European psycho dramas that always conclude in extremis by an agreement that is supposed to save Greece and the euro zone. From the beginning, it was clear that a method based on the administration of massive doses of austerity without any real support for the modernization of the Greek economy was doomed to failure [1], for reasons that are now well understood [2] but at the time were almost universally ignored by officialdom, whether from European governments, the European Commission or the IMF, the main guarantor and source of inspiration for the successive adjustment plans.

The results, which up to now have been catastrophic, are well known: despite the lengthy austerity cure, consisting of tax hikes, public spending cuts, lower wages and pensions, etc., the Greek economy, far from recovering, is now in a worse state, as is the sustainability of the country’s public finances. Despite the agreement in 2012 of Europe’s governments on a partial default, which reduced the debt to private creditors – relief denied by those same governments two years earlier – Greece’s public debt now represents a larger percentage of GDP (almost 180%) than at the beginning of the crisis, and new relief – this time probably by rescheduling – seems unavoidable. The third bailout package – roughly 85 billion euros, on the heels of approximately 250 billion over the past five years – will be negotiated over the coming weeks and will be in large part devoted just to meeting debt repayments.

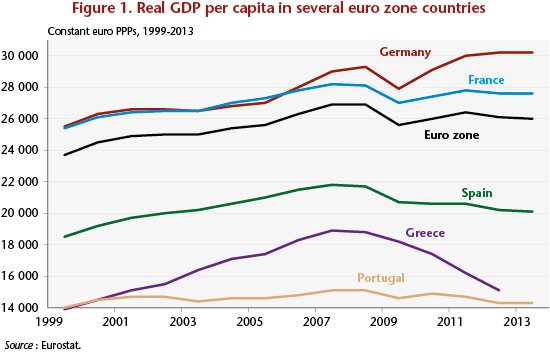

Meanwhile, the average living standard of Greeks has literally collapsed; the difference with the euro zone average, which had tended to decline during the decade before the crisis, has now widened dramatically (Figure 1): the country’s GDP per capita is now a little less than half that in Germany. And GDP per capita still only poorly reflects the reality in an economy where inequality has increased and spending on social protection has been drastically reduced.

The new austerity plan is similar to the previous ones: it combines tax hikes – in particular on VAT, with the normal rate of 23% being extended to the Islands and many sectors, including tourism, that were previously subject to the intermediate rate of 13% – with reduced public spending, and will result in budget savings of about 6.5 billion euros over a full year, which will depress domestic demand and exacerbate the current recession.

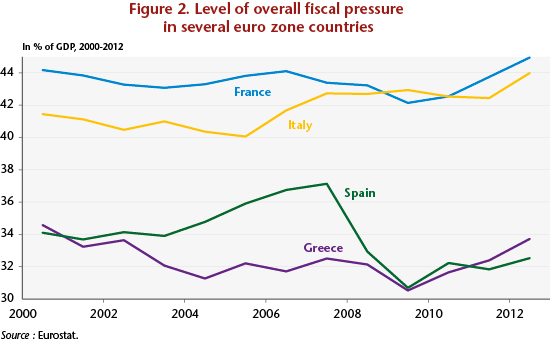

The previous adjustment plans also featured “structural” reforms, such as lowering the minimum wage and pensions, deregulation of the labour market, etc. But it is clear that the fiscal component of these plans did not have a very visible impact on government revenue: after having declined significantly until 2009, the Greek tax burden – measured by the ratio of total tax revenue to GDP – has definitely increased, but not much more than in France (Figure 2). This does not mean, of course, that an even stronger dose of the same medicine will lead to better healing.

Does history shed light on the future?

The ills afflicting the Greek economy are well known: weak industrial and export sectors – apart from tourism, which could undoubtedly do better, but performs honourably – numerous regulated sectors and rentier situations, overstaffed and inefficient administration and tax services, burdensome military expenditure, etc.

None of this is new, and no doubt it was the responsibility of the European authorities to sound the alarm sooner and help Greece to renovate, as was done for the Central and Eastern Europe countries in the early 2000s in the years before they joined the European Union. Will the way it has been decided to do this now, through a forced march with the Greek government under virtual guardianship, be more effective?

If we rely simply on history, the temptation is to say yes. There are many similarities between the situation today and a Greek default back in 1893. At that time Greece was a relatively new state, having won its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1830 following a long struggle supported by the European powers (England and France), which put the country under a Bavarian king. Greece was significantly poorer than the countries of Western Europe: despite an effort at modernization undertaken after independence that was led by the Bavarian officials assembled around the Greek King Otto, in 1890 the country’s GDP per capita was, according to data assembled by Angus Maddison[3], about 50% of the level of France, and a little less than one-third that of the UK. The analysis of Greece at that time was little better than that today:

“ … Greece has been characterized throughout the 19th century by structurally weak finances, which has led it to default repeatedly on its public debt. According to the Statesman’s Yearbook, in addition to significant military spending, Greece faces high expenditures on a disproportionately large number of officials for a small undeveloped state. Moreover, since part of Greece’s debt is guaranteed by France and Great Britain, Greece could suspend debt service without the creditors having to suffer the consequences. The French and British budgets would be compelled to pay the coupons.

“By 1890, however, the situation had become critical. At the end of 1892, the Greek Government could continue paying interest only by resorting to new borrowing. In 1893, it obtained parliamentary approval for negotiating a rescheduling with its international creditors (British, German, French). Discussions were drawn out until 1898, with no real solution. It was Greece’s defeat in the country’s war with Turkey that served as a catalyst for resolving the public finances. The foreign powers intervened, including with support for raising the funds claimed by Turkey for the evacuation of Thessaly, and Greece’s finances were put under supervision. A private company under international control was commissioned to collect taxes and to settle Greek spending based on a seniority rule designed to ensure the payment of a minimal interest. Fiscal surpluses were then allocated based on 60% to the creditors and 40% for the government.”[4]

Between 1890 and 1900, Greek per capita income rose by 15% and went on to increase by 18% over the next decade; in 1913, it came to 46% of French per capita income and 30% of the British level, which was then at the height of its prosperity. So this was a success.

Of course, the context was very different then, and the conditions that favoured the guardianship and the recovery are not the same as today: there was no real democratic government in Greece; there was a monetary regime (the gold standard) in which suspensions of convertibility – the equivalent of a “temporary Grexit” – were relatively common and clearly perceived by creditors as temporary; and in particular there was a context of strong economic growth throughout Western Europe – what the French called the “Belle Epoque” – thanks to the second industrial revolution. One cannot help thinking, nevertheless, that the conditions dictated to Greece back then inspired the current decisions of Europe’s officials[5].

Will the new plan finally yield the desired results? Perhaps, if other conditions are met: substantial relief of the Greek public debt, as the IMF is now demanding, and financial support for the modernization of the Greek economy. A Marshall Plan for Greece, a “green new deal”? All this can succeed only if the rest of the euro zone is also experiencing sustained growth.

[1] See Eloi Laurent and Jacques Le Cacheux, “Zone euro: no future?”, Lettre de l’OFCE, no. 320, 14 June 2010, http://www.ofce.sciences-po.fr/pdf/lettres/320.pdf .

[2] See in particular the work of the OFCE on the recessionary effects of austerity policies: http://www.ofce.sciences-po.fr/pdf/revue/si2014/si2014.pdf . Recall that the IMF itself has acknowledged that the adjustment plans imposed on the European economies experiencing public debt crises were excessive and poorly designed, and especially those imposed on Greece. This mea culpa has obviously left Europe’s main leaders unmoved, and more than ever inclined to persevere in their error: Errare humanum est, perseverare diabolicum!

[3] See the data on the Maddison Project site: http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm .

[4] Excerpt from the article by Marc Flandreau and Jacques Le Cacheux, “La convergence est-elle nécessaire à la création d’une zone monétaire ? Réflexions sur l’étalon-or 1880-1914” [Is convergence necessary for the creation of a monetary zone? Reflections on the gold standard 1880-1914], Revue de l’OFCE, no. 58, July 1996, http://www.ofce.sciences-po.fr/pdf/revue/1-58.pdf .

[5] An additional clue: the German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble insisted that Greece temporarily suspend its participation in the euro zone; in the 1890s, it had had to suspend the convertibility into gold of its currency and conducted several devaluations.