By Henri Sterdyniak

In June 2014, the government had Parliament approve a new provision for the gradual reduction of employee payroll taxes intended to boost the purchasing power of low-wage earners. Henceforth an employee on the minimum wage (SMIC) would benefit from a 3-point reduction in their contributions, representing a gain of 43 euros per month, i.e. a 4% increase in net income. The discount would then decline with the level of the hourly wage and terminate at 1.3 times the SMIC. On 6 August 2014, the Constitutional Council (Conseil Constitutionnel) barred this provision. There are three reasons to welcome its ruling.

As noted by the Constitutional Council, employee contributions fund retirement and replacement benefits, social insurance programmes that are reserved for those who have contributed and which depend on contributions. The parliamentary measure goes against the logic of a contributory system, since employees would have been able to enjoy benefits without having fully paid.[1] The Constitutional Council emphasized the specific nature of contributory social contributions, underscoring a sound principle of our social security system. Note, however, that the Constitutional Council did not oppose the measures exempting employer social contributions for pension contributions, which are also based on a contributory logic. On the other hand, the exemptions on family or health insurance contributions are more legitimate, since these contributions do not confer individual rights. But it’s never too late to correct one’s oversights.

The new measure planned by the government once again led to reducing the resources of the social security system. Exemptions from social security contributions have become the weapon of choice against unemployment, to the expense of the very purpose of the contributions: to fund social security. The State would of course have offset these exemptions, but social security would have become even more dependent on government transfers, particularly since this measure came on top of the extension, for the years 2013 and 2014 alone, of employer payroll tax cuts and transfers of resources from the taxation of family pension increases and the reduction of the family quotient.

Finally, this exemption would have introduced a new complication for pay slips, which already count twenty lines for contributions. In addition, employers must calculate digressive exemptions on employer contribution, from 28 points at the SMIC level up to 1.6 times the SMIC, and in addition the competitive employment tax credit (CICE) of 6% for wages under 2.5 times the SMIC. From 2016, family contributions will be lowered by 1.8 points for wages under 3.5 times the SMIC. Is an even more digressive system really needed, with a new ceiling of 1.3 times the SMIC?

Despite the Council decision, the government has not abandoned its goal. Thus, in an article in Le Monde dated 21 August 2014, President François Hollande announced a reform “that will merge the Prime pour l’emploi (PPE) and the Revenu de solidarité active (RSA) to promote the return to work and improve the situation of precarious workers”. Would a reform like this fulfill the President’s objectives? To answer this question it is useful to review the existing arrangements.

The current situation

France has set up a particularly complicated system that aims at two somewhat contradictory goals: to help poor families and to encourage unskilled workers to find jobs.

Aid to the poorest households includes the Revenu de solidarité active (RSA – a family-based income supplement for the working poor), the Prime pour l’emploi (PPE – an individual in-work tax credit to promote employment), housing benefit (a family-based allowance) and means-tested family benefits (family income supplement, allowance for school). Despite the efforts of Martin Hirsch, the RSA’s promoter, it does not include the PPE and housing benefit. It consists of a basic allowance: the base RSA (RSA socle – a minimum income that depends on family composition), which is reduced by 38 euros per 100 euros of earned income. The RSA is paid monthly on the basis of a quarterly income statement. As for the PPE, it is paid automatically on the basis of the income tax return, with a one year lag. The RSA is deducted from the PPE, meaning that a household that does not ask for the RSA automatically gets the PPE.

Three mechanisms are specifically designed to encourage low-wage workers to find jobs: exemptions from employer contributions, which reduce the cost of labor at the SMIC level; and the PPE and the RSA, which increase the gain from employment for unskilled workers.

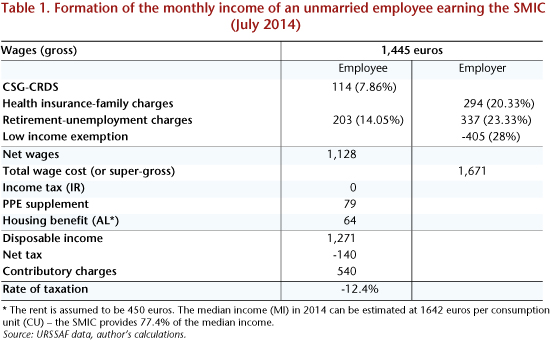

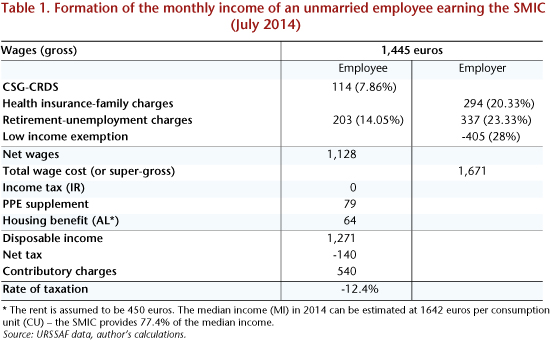

A single person paid the SMIC is entitled to the PPE, but not the RSA (Table 1). It costs the company 1,671 euros (for 35 hours); the person’s salary incurs 540 euros in unemployment and retirement contributions, representing deferred wages; the person receives a net transfer of 140 euros (PPE + housing benefit – CSG-CRDS [CSG wealth tax and CRDS debt contribution] – national health insurance and family contributions); their disposable income thus comes to 1,271 euros. There is therefore no net tax burden; their health insurance is offered. The exemptions of employer contributions are higher than the non-contributory contributions. By making use of all the existing schemes, it is possible to dissociate the living standard accorded to workers on the SMIC from the cost of their work.

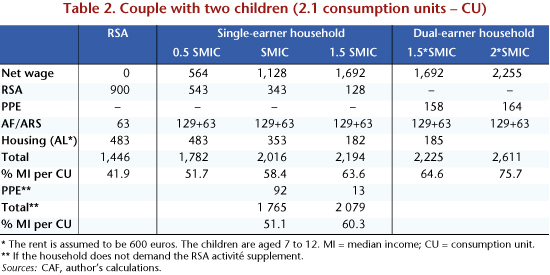

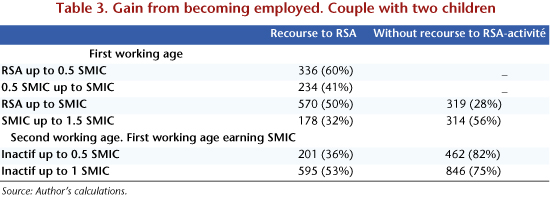

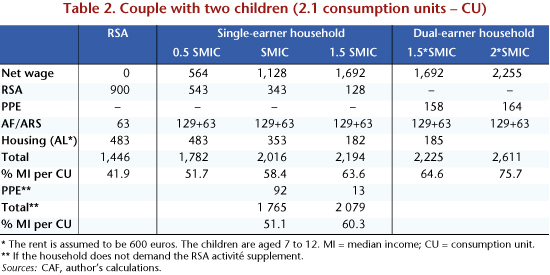

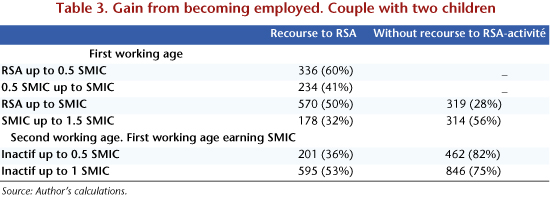

On the other hand, a single-earner family (Table 2) benefits from the RSA so long as the household income does not exceed 1.65 times the SMIC (Table 2). The RSA increases the incomes of the poorest households: it increases the gains from employment for the first earner, but slightly reduces those of the second (Table 3). The PPE benefits dual-earner families that are above the poverty line (defined as 60% of the median income).

The limits of the existing system

– The reduction of employer contributions: The PPE and RSA create a class of poorly paid employees whose salary increases are very costly for the employer and not very profitable for the employee. A 10% wage hike for a worker on the SMIC (145 euros) costs the company 242 euros and brings the employee 53 euros. Companies are encouraged to create specific unskilled jobs, with no prospects for progress for the employee, who is stuck in a low-wage trap. The reduction in charges on low wages does not promote the employment of skilled workers, who are also experiencing some unemployment. Not do the jobs created match up with the increasing qualifications of young people. The consistency of the system as a whole therefore needs to be reviewed. However, the persistence of a large mass of unskilled workers and the desire not to lower the living standards of the working poor currently make it hard to take the risk of eliminating the existing mechanisms.

– The calculation of the PPE is complicated: It is paid only after a year’s delay, meaning that the incentive effect is probably very small. This supplement benefits employees above the poverty line rather than the poorest families. At the same time, eliminating it would decrease the living standard of those on the SMIC by 6%, which is not an option.

– The rate of non-take-up of the RSA-activité is very high (about 68%)[2]. Low-wage workers refuse to be subjected to ongoing monitoring just to receive a relatively small amount of benefit. Given some stigmatization of those receiving the RSA, these workers do not want to be confused with people receiving the base RSA (RSA-socle).

– The RSA provides a benefit of around 110 euros per child for families with 1 or 2 children receiving the minimum wage, a benefit that fills a gap in our system, which was not very generous for families of the working poor. But this benefit is not paid to unemployed families. This 110 euro allocation should be paid in the form of a family supplement to all poor families with 1 or 2 children (families with 3 or more children already have a family income supplement and more generous benefits) regardless of the source of income.

– The RSA is not paid to people under age 25, even though this age group has particular difficulty finding jobs.

What is to be done?

As France has such a large number of social benefits and charges, it is possible to target the measure precisely depending on the objective. Several measures can be envisaged:

Increase family benefits

If the goal is to increase the purchasing power of poor families, the easiest way to do this is to significantly increase family and housing benefits. Instead, the government has decided to suspend their indexation in 2014 or 2015, inflicting a loss of purchasing power, which fortunately will be limited by low inflation. But the prevailing view today is that it is essential to encourage employment, and thus to increase net wages rather than benefits.

Lower income tax

As poor families do not pay income tax, lowering it will not affect them.

Make the CSG wealth tax progressive

As shown in Table 1, a minimum wage worker pays 114 euros in CSG-CRDS and receives 79 euros in PPE. Wouldn’t it be possible to offset the removal of the PPE by making the CSG progressive, which would exempt workers on the SMIC and increase the wages they receive each month? The Constitutional Council rightly considers that any progressive tax must be family based and take into account all the family income. A genuinely progressive CSG is thus virtually impossible to implement, as employers and financial institutions would need to know the marital status of their employees and customers and all of their income, making everyone repeat the work of the tax authorities. This would only make sense in the context of a CSG-income tax merger, which is not feasible in the short term.

Furthermore, only limited progressivity would be feasible. Each person would be entitled to an exemption of around 1,445 euros per month on the amount of income subject to the CSG-CRDS; a spouse without their own resources could transfer their exemption to their partner; dependent children would be eligible for a half exemption. In return, the PPE would be eliminated; pensioners and the unemployed could be subject to the same CSG as employees. But this exemption would have a huge cost, and in return the rate of the CSG would need to rise to 15% on income above the exemption. This possibility thus must be abandoned.

The merger of the PPE and RSA

The fusion of the PPE and RSA is the path proposed by the President of the Republic. But the devil is in the details, in how to fashion the merger.

In 2013, the report of MP Christopher Sirugue proposed a reform that would create an activity bonus (Prime d’ activité) to replace the RSA-activité and the PPE (see the critical analysis of Guillaume Allègre, Faut-il remplacer le RSA-activité et la PPE par une Prime d’activité? Réflexions autour du rapport Sirugue, 2013). However, as the base RSA would continue to exist, families with very low wages would need to seek two benefits – the base RSA and the Prime d’activité – confronting them with a complicated system. The benefit schedule for Prime d’ activité set out in the Sirugue report was arbitrary, with slopes and a peak at 0.7 SMIC that had no justification. The resulting system was more complicated and more arbitrary than the RSA, and did not represent any major improvement over the existing system. The proposed measure was costly for single-income families (some lost 10% of their income). The risk was that the Prime d’activité would suffer from the same lack of take-up as the PPE and that some families would lose the PPE without wanting to use the Prime d’activité [3].

A merger that would result in a family-based benefit paid by France’s Family Allowance Fund (CAF) would run the risk of a high rate of non-take-up and would generate losers among dual-earner households with children. A merger that would result in an allowance paid on the pay slip would not take into account children and the spouse, and would hurt part-time workers, raising questions about consistency with the base RSA.

In short, the merger is tricky to implement (if not impossible).

Increase the SMIC[4]

If the goal is to increase the living standard of low-wage earners, the obvious measure is to raise the level of the SMIC. An increase of about 10% would make it possible to eliminate the PPE and provide minimum-wage workers an increase in income equivalent to that under the measure overruled by the Constitutional Court. Assistance aimed specifically at part-time workers would be abandoned, as with the PPE, but this specific assistance is too complicated to have any incentive effect at all. An increase in net earnings is undoubtedly better.

Note, however, that an increase in the minimum wage would not provide enough support for poor families with one or two children, especially the families of the unemployed. The families of the working poor (between the base RSA and 2 times the SMIC) need specific support, by introducing a family supplement of about 80 euros for one child and 160 euros for two children.

The RSA-activité should be maintained, since it ensures that any activity actually results in higher disposable income, but its role would be reduced and, thanks to the extension of the family income supplement, non-take-up would have less impact on families with children.

It is also necessary to create an employment integration allowance, in the amount of the RSA, for young people seeking work, without a right to unemployment benefit, a benefit subject to pension contributions.

Nevertheless, in the current situation, where lowering labor costs is a top priority for government policy, the cost of unskilled labor cannot be increased, leaving two possible approaches.

Either compensation for employers would take place through an increase in exemptions on charges on low-wage workers (which are to rise from 28% to 34.6%), which would not introduce an additional scheme. However, the exemptions on employer contributions would focus on contributory contributions, which could arouse the ire of the Constitutional Court.

Or the increase of the SMIC would take place through a PPE listed on the pay slip: it would be explicitly recognized as a supplement, which implies that the compulsory tax burden would increase, but also that the Constitutional Court could not oppose it, with the drawback that the supplement would fall with the level of the hourly wage, thus representing an additional administrative burden for business.

It seems obvious that there are no simple solutions.

[1] The Constitutional Court wrote, “… a single social security system would continue under the provisions in question, to finance, for all of its stakeholders, the same benefits despite the absence of payment by nearly one-third of them of all the employee contributions conferring entitlement to the benefits paid by the system; that, therefore, the legislature has created a difference in treatment, which is not based on a difference in the situation of those insured by the same social security scheme, and which is unrelated to the purpose of employee social security contributions.”

[2] According to P. Domingo and M. Pucci, 2012, “Le non-recours au revenu de solidarité active et ses motifs”, Annex no. 1 of the Report of the Comité national d’évaluation du Rsa.

[3] The Rapport sur la fiscalité des ménages by François Auvigne and Dominique Lefebvre, 2014, also points out deficiencies in the project.

[4] This is already the strategy recommended by Allègre (2014).