By Françoise Milewski

The deterioration of the labour market since the start of the crisis has hit men and women differently. Recent trends show that adjustments are being made in different ways. Gender inequalities are producing differentiated trends in employment and unemployment, which is leading in turn to specific forms of inequality.

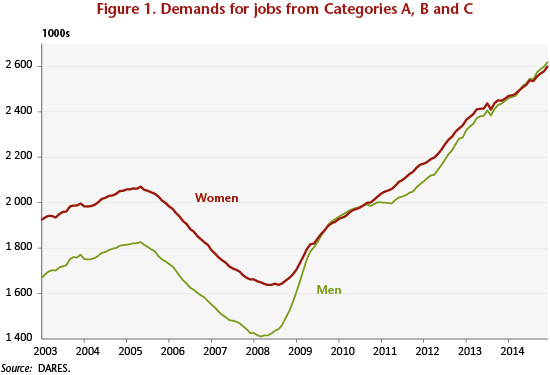

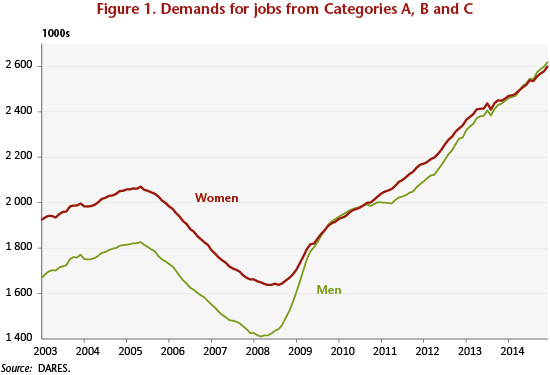

Since spring 2008, category A job searches [1] have increased for both men and women, but much more for the former (93% against 60%). The trend was more uneven for men under the influence of the business and public policy cycles, especially partial unemployment measures.

Men jobseekers have outnumbered women jobseekers since November 2008. In December 2014, men represented 52.9% of jobseekers. But this breakdown is close to their respective shares in the labour force and in employment. It is the previously existing situation that was abnormal: women, a minority on the labour market, had been a majority in category A unemployment.

Despite this, job searches by those on low hours [2], that is to say, people who have a part-time job but are registered at the job centre because they want to work more, are mostly by women (55.4%); this proportion has not changed much from before the crisis. Women are also over-represented in category B, short-term low-hours jobs. The increase in job applications from those on low hours was slower and less uneven than those in category A. It was also less differentiated by gender.

Overall, if we take into account demands for jobs from categories A, B and C, there have been slightly more men jobseekers than women since summer 2014 (50.2% in December 2014). This is a new feature of the labour market (Figure 1).

This characteristic holds true for those who are under age 25 and age 25 to 49. In contrast, more women over the age of 50 are unemployed than men, due to the high level of job applications from those working low hours.

The impact of the lack of gender diversity of professions and employment sectors

These trends are due to changes in employment. Women are concentrated in the service sector, and men more in industry and construction. But the greatest job losses have occurred in industry and construction. The services, which are traditionally less cyclical, have seen fewer job losses, and even some job creation in a few years (from 2010 to 2012 and then in 2014) if interim work is reassigned to the user sectors. This job creation has been on a small scale, but women’s employment has suffered less from the crisis, or at least in a different way. It fell in 2009, then increased slightly, and then stabilized. This is of course a break in the trends for growth rates in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, but there is a clear difference with men’s employment, which fell significantly in 2009 and again in 2012 and 2013. The 1980s and 1990s were already not favourable years for men’s employment.

Single-sex trades result from the gender-biased school experience and job training, and reinforce this in return. This explains why there are such great differences in job opportunities between sectors. Service jobs, particularly personal services, are the preserve of women: their supposedly “innate” skills lead them to do in the commercial sphere what they are already doing in the family sphere: upbringing, educating, caring for others, cleaning, etc.

Inequalities in career guidance thus have a “positive” counterpart in employment, at least if we confine ourselves to the volume of jobs. But the poor quality of certain jobs and their under-valuation also stems from this.

A trend in employment rates favouring women

The participation and employment rates can be linked with the unemployment rate (according to the ILO [3]) in order to clarify both the differences between women and men and the profound differences by age group.

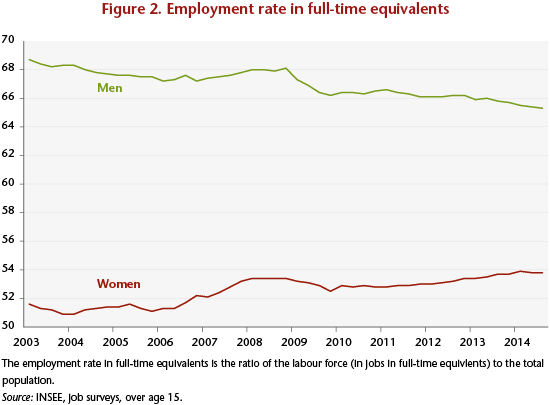

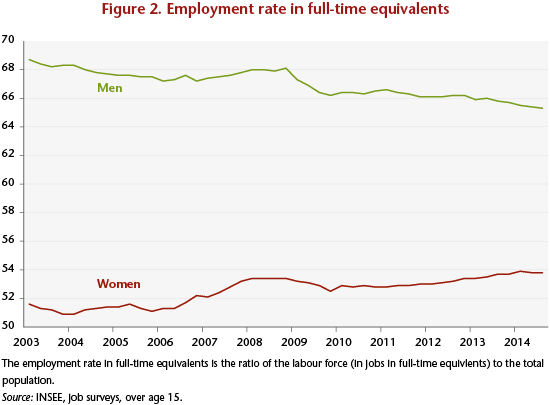

Taking all ages combined, women have increased their labour force participation rates over the period 2008-2014 (2.3 points). Their employment rate fell between 2008 and 2010 and then recovered to exceed its pre-crisis level. The unemployment rate thus rose sharply in the initial period of the crisis, then stabilized before rising again since early 2012, with the increase in the employment rate remaining lower than in the participation rate. The full-time employment rate at first declined and then stabilized, while the rate of part-time employment rose slightly. The share of part-time employment is up from early 2008, but only by 1 point.

With respect to men, the participation rate increased very slightly (+0.6 point) while the employment rate decreased significantly (-2.1 points), resulting in the greater increase in unemployment. The decline in men’s employment rate is associated essentially with full-time employment. As the level of part-time employment is still very low, its increase has had little impact on the overall picture. The share of part-time employment for men did, however, rise from 5.5% in spring 2008 to 8% in the third quarter of 2014.

The employment rate in full-time equivalents is therefore diverging: the rate for men fell over the period, while women’s rate, following a decline at the start of the crisis, has been picking up at a moderate but steady pace since 2011 (Figure 2).

The “halo” around unemployment[4] has grown, particularly among men (+37.4% compared with +8.8%), but women are still over-represented in it (56.9% of the total at end 2014).

However, these averages reflect trends that differ greatly by age group. The stabilization of the male participation rate is the result of a decline for both young people and those aged 25-49 together with a rise for those over age 50. But the rise in the employment rate of older workers has not been sufficient to offset the decline in other categories. For women, only the participation rate for those aged 15-24 has been declining, and the higher employment rates of those over 50 has offset the decline in the rates for both young people and, more moderately, for those age 25-49.

Older employees have been especially affected

The labour force participation, employment and unemployment of older workers are atypical because this age group’s position has been weakened by the impact of the later retirement age. The trends in unemployment rates have been similar for both genders, including in terms of volume. The participation rate has risen steeply since 2009: for men, this follows a long period of decline until 1995, then a rise due to the 1993 pension reform, followed by a renewed decline (moderate) between 2003 and 2008. The rise since 2009 petered out in 2013 and 2014 (due to the end-of-work measures affecting workers age 60 with lengthy careers, which in practice mainly affected men). For women, the increase has been continuous since 1990: after plateauing between 2005 and 2008, the rise picked up pace, without the tapering-off seen at the end of this period for men. The steadier increase for women reflected the rise of the participation rates of the younger generation in previous decades. The employment rates have not risen as steeply as the participation rates, as unemployment has increased for both sexes. The difficulty of finding a job has also pushed up part-time employment rates, especially for women. The share of part-time employment reached 10.2% for men at the end of the period (still significantly below women’s rate: 33.4%).

The unemployment rate of 25-49 year-olds increased for both sexes, especially for men, leading to a convergence in rates since end 2012. However, men’s activity rate declined slightly since the beginning of the crisis, in contrast to women’s rate, which on average stabilized over the period. The fall in employment rates was very marked for men (-5.2 points), and less so for women (-1.7). This was also the case for full-time employment rates. The share of part-time employment has been increasing a little for men, but is still very low (just over 5%), while it has stabilized for women. The employment rates in full-time equivalents have changed very differently: the rate has fallen steeply for men, but only a little for women. The deterioration in the volume of employment is thus hitting men in particular. But the levels are still very different.

Young women do not benefit as much from their education

The unemployment rates for men and women under age 25 converged in the early 2000s, in contrast to other age groups. Since then, they have tended to evolve similarly. The level of the labour force participation rates differs significantly, with women’s rate still about 7 percentage points below that of men. The participation rates have declined in tandem since the crisis began, as have employment rates. Young people who are unable to find jobs are prolonging their education.

It is the rate of full-time employment that has declined the most, especially for young men. The part-time employment rate failed to offset this decline: it remained stable for men, except since the end of 2012, when it rose slightly, while it decreased for women (but only moderately).

It is striking to see the large difference in the respective levels of part-time employment even at this age (about 4 points). But the cause is not parental duties! The reason needs to be sought instead in the nature of the jobs associated with different professions and industrial sectors. Part-time work as a share of all employment came to nearly 35% for women at year-end, against 17% for men. This, however, is up sharply over the last six quarters. It is too early to say that this represents a rupture with previous trends, with the crisis leading young men to take jobs that they previously refused, or that they are shifting more towards service sector work that hasn’t been hit as hard.

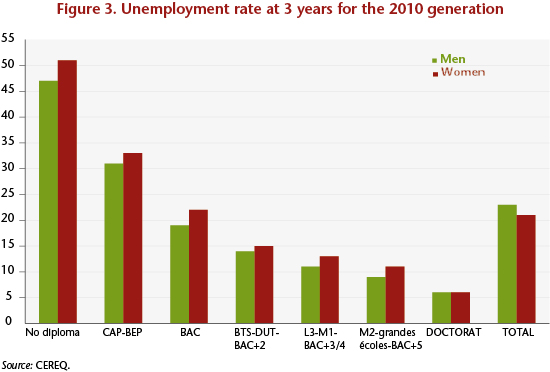

The level of training is to the advantage of women. Yet it is clear, first, that a diploma offers protection against unemployment and the crisis (the highest unemployment rates are among those with few or no qualifications), and second, that girls do better in school and on average graduate more frequently. How then is it possible to explain that the unemployment rate is equivalent for men and women? An INSEE study on career starts was conducted in 2010 over the period 1984 to 2008[5]. It showed that in the early 1980s significantly more women were unemployed relative to men during the initial five years of working life, but that the gap has narrowed, with the unemployment rates converging in 2002. In 2007 and 2008, the female unemployment rate had fallen even lower than that of men at career start, thanks to the rise in their educational level. For the same level of training, young men usually fare better on the labour market: young women still tend to have higher unemployment rates and lower salaries because of the educational specialties they have chosen. The INSEE estimated that for identical degrees, specialties and job lengths, women’s risk of unemployment was 7% higher than for men during their initial years of work.

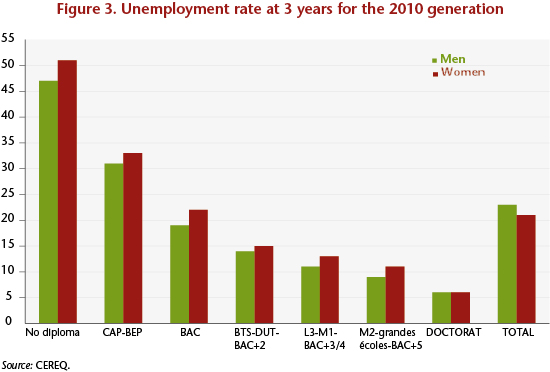

What about since the crisis? The CEREQ conducts work surveys on the future of young people leaving the education system. The last of these “Generation surveys” was conducted in 2013 on the 2010 generation[6]. It shows a worsening situation due to the crisis and very sharp differences by degree level. In 2013, three years after leaving school, 22% of young people were still hunting for work. This is the highest level ever seen in the CEREQ surveys. The increase over the 2004 generation was 16 points for young people without degrees and 3 points for long-term higher education graduates.

Better-educated women are standing up to the crisis better. For the 2010 generation (contrary to the 2004 generation), the employment rate for men decreased so as to match women’s rate, and the unemployment rate for women is lower than that for men. Young men are more exposed to long-term unemployment. Women’s relative advantage is due to their higher level of schooling, which has risen more than that for men.

But there are persistent inequalities in the labour market, to the disadvantage of women: for comparable schooling at any level (from non-graduates to high school diploma +5 years, except the PhD level), the unemployment rate for women is higher than for men (Figure 3). Thus, women’s lower level of unemployment is due only to their higher level of education, which does not have a full impact.

A reconfiguration of inequality

The inequalities between women and men are shifting, but persistent. Unemployment has increased less among women during the crisis than among men. This is due, first, to the sectoral distribution of their jobs (especially in the service sector) and to single-sex trades. Second, raising the average level of education has enabled women to withstand the crisis better, but the magnitude of this effect is lower than it should be. It is therefore not enough to wait for time to do its work: even among the young generations, there is still discrimination in hiring and in the initial years of working life. Unless, of course, we await a time (hypothetical and hardly desirable) when generations of highly skilled women will exist side by side with generations of unskilled men, and labour market inequalities finally diminish…

Job quality is also a real challenge: part-time work is spreading among men, especially the older and younger age groups, but it is still particularly widespread among women, who continue to assume most parental duties. But part-time work is also more common among women under age 25 who are not yet in this situation.

Service jobs, particularly personal services, offer opportunities for the less skilled, but often part-time. Do we really want women to more readily accept “poor” jobs?

What is taking place is, therefore, a reconfiguration: women are improving their educational level, and the increasing numbers of them with higher qualifications are becoming a stable part of the workforce. However, they benefit less from their training, not only in terms of their salary and career progression, but even when they first begin their working lives, including in terms of employment and unemployment. Less-qualified women are at a particular disadvantage and form the core of the “precariat”, which is growing. Deregulating the labour market tends to amplify inequalities by forcing those in a weaker position on the labour market to accept part-time work with reduced hours on a large scale. So it is not enough to wait for inequalities to disappear or even diminish.

[1] Category A: Job seekers registered at the French Pôle emploi job centre who are unemployed and required to conduct a positive job search.

[2] Job seekers registered at the French Pôle emploi job centre who are required to conduct a positive job search and have worked fewer hours (78 hours or less during the month) for category B, or more hours but less than full time (more than 78 hours in the month) for category C.

[3] An unemployed person within the meaning of the International Labour Office (ILO) is a person of working age (15 or older) who has not worked, even for one hour, during the given week, is available for work within two weeks, and has begun an active job search in the previous month (or found a job that starts within three months). The unemployment rate is the ratio between the number of unemployed and the number of people in employment (employed or unemployed).

[4] The halo around unemployment includes people who do not have jobs and want to work but who are not considered unemployed by ILO standards as they are not available to work within two weeks and / or are not seeking work.

[5] “Femmes et hommes en début de carrière. Les femmes commencent à tirer profit de leur réussite scolaire” [Women and men at the start of the career. Women are beginning to benefit from their success at school], Alice Mainguené and Daniel Martinelli, Insee Première, no. 1284, February 2010, http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/document.asp?ref_id=ip1284.

[6] “Face à la crise, le fossé se creuse entre niveaux de diplôme” [In the face of the crisis, the gap is increasing between diploma levels], Christophe Barret, Florence Ryk, Noémie Volle, Bref CEREQ no. 319, March 2014, http://www.cereq.fr/index.php/publications/Bref/Enquete-2013-aupres-de-la-Generation-2010-Face-a-la-crise-le-fosse-se-creuse-entre-niveaux-de-diplome.