Do separated fathers bear a greater sacrifice in their standard of living than their ex-partners?

by Hélène Périvier OFCE-PRESAGE

The recent study published by France Strategy on the sharing of the costs of children after a separation has caused a stir (see in particular Dare feminism, Abandoning the family, as well as SOS Papa [all in French]). The study analyses the changes in the standard of living of both the former spouses, taking into account the interaction between the indicative scale for child support and the tax-benefit system. This approach is stimulating, as it endeavours to see whether the redistribution effected through the welfare state fairly and equitably deals with the costs of the child borne by each former spouse.

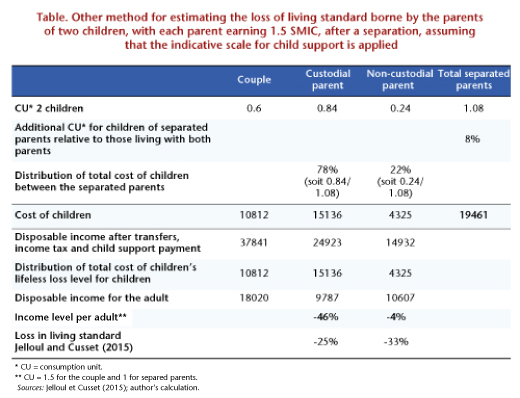

It is reported that after separating, the living standards of the two former partners fell sharply. In addition, simulations of typical cases “indicate that as a result of applying the scale [the indicative reference scale provided to judges] under existing social and tax legislation, the care of children causes a significantly greater sacrifice in the standard of living of the non-custodial parent than of the custodial parent”. In other words, separated fathers are making a greater sacrifice in their standard of living than are the mothers, if the judge were to apply the indicative scale to the letter. But according to the Ministry of Justice the scale is not applied by judges, as both situations are always very specific. So the study looks at what the standard of living of the separated parents would be if the scale were applied, and not at their actual standard of living. However the table of results presented in the note on the front page is titled, “Estimating the loss of living standards incurred by the parents of two children (as a percentage compared to the situation with no child, calculation net of state aid)”. Someone reading this quickly could easily think this was the real situation of separated parents.

Even though the study is based on the scale for support payments and not on the decisions of the judges themselves, it raises a relevant question. But the results are weakened by significant methodological problems: the concept of the sacrifice in the standard of living does not take into account the gender division of labour and its impact on mothers’ careers; the typical cases highlighted are not necessarily representative (in particular concerning marital status prior to separation); using the equivalence scales [1] leads to conflating the “household standard of living” and “the individual standard of living”; and finally, an approach based on maintaining the child’s standard of living would have led to a completely different result. Ultimately, proposing the micro-simulation model as an aid to the judges’ decision-making seems somewhat premature in light of these criticisms.

On the concept of “a sacrifice in the standard of living”

In all the cases simulated, the separated parents’ living standards go down relative to their situation as a couple (assuming unchanged income). This result is consistent with other recent work, such as Martin and Périvier, 2015; Bonnet, Garbinti, Solaz, 2015; and the report of France’s Family Council (the HCF). A separation is costly for both parents due to the loss of economies of scale (e.g. two homes are needed instead of one, etc.). In addition to the decline in living standards for each parent, the authors calculate the “sacrifice in living standards” experienced by the parents after the separation.

The “living standard sacrifice” is supposed to be calculated by comparing the cost of the child to the disposable income that the parent would have had if there were no child. However, the living standard sacrifice made by the mother with custody of the child (or the father, respectively) is actually calculated by comparing the child’s cost with the standard of living of a single woman without children with the same salary level as the separated mother (and the same for the father).

This method cannot be used to estimate the “living standard sacrifice”, since forming a couple and a family are accompanied by a gender division of labour, which has been widely documented in the literature and which implies that the separated wife has a salary level, and more generally a career, that is different from what she would have had if she had remained single with no children. If a woman senior executive living in a couple stops working in order to look after the children and then the couple separates, the concept of the “living standard sacrifice” would imply a significant gain in the quality of life for this woman, since the cost of the children would be relative to the RSA minimum income, whereas she would have received a higher salary if she had not had children because she would have continued to work.

In other words, the proper counterfactual, that is to say the situation with which we must compare the level of the separated parent so as to assess the living standard sacrifice that she (or he) suffers, should be the income that the woman (or man) would have had when separated (taking into account their individual characteristics) if she (or he) had not entered a couple and if she (or he) had not had children. By doing this, the calculations would have led to a significantly greater sacrifice by the woman than that calculated in the study. Here we see the need for an economic approach that integrates the behaviour of agents, compared with an accounting approach.

Atypical typical cases?

The authors used the micro-simulation model Openfisca to simulate different situations and assess the loss in living standard by each former spouse after the separation.

The typical cases are used to understand the complex interactions between the tax-benefit system and, for the subject matter here, the indicative scale of child support payments. The criticism usually made of typical case studies is that they do not reflect the representativeness of the situations simulated: so to avoid focusing on marginal cases, data is added about the frequency of the situations selected as “typical”. With respect to the distribution of income, in three-quarters of the cases the women earn less than their male partners (Insee). What would be needed is to look at the distribution of income between spouses before the break and see what are the most common cases and then to refine the operation by retaining only those cases where the judge sets a support payment, i.e. in only 2 out of 3 cases (Belmokhtar, 2014).

Likewise, focusing on the case of a couple with two dependent children is not without consequences[2], since with only one dependent child the amount of family benefits falls, meaning that the social benefits received by the mother would be lower (in particular the family allowance is paid only starting from the second child) as would her standard of living. Statistics provided by the Ministry of Justice indicate that the average number of children is 1.7 in the case of divorces and 1.4 in the case of common-law unions (Belmokhtar, 2014).

Finally, nothing is said explicitly about the marital situation prior to the separation: marriage or common-law?

– Either the authors are considering married couples. In this case, if the salaries of the ex-spouses are different (case 4 described as “Asymmetry of income”), how is the loss of France’s marital quotient benefit (quotient conjugal) distributed? After divorce, the tax gain resulting from joint taxation is lost: the man then pays a tax amount based on his own salary and no longer on the couple’s average salary. This additional tax burden hits his living standard, and the “living standard sacrifice” calculated for the divorced father would then partly reflect the loss of this marital quotient benefit, and not the cost arising from the expense of a separated child.

– Or the authors consider only common-law couples, which seems to be the case given the vocabulary used – “separation, union, separated parents, etc.” – but then this brings back the criticism about the representativeness of the typical cases, since more than half of the court decisions regarding the children’s residence are related to divorces (Carrasco and Dufour, 2015). Moreover, the support payments set by the judge are all the more distant from the scale in the case of a separation and not a divorce, which limits the scope of the study.

On the proper use of equivalence scales

Equivalence scales are used to compare the living standards of households of different sizes, by applying consumption units (CU) to establish an “adult equivalent”. These scales are based on strong assumptions that do not allow the use of this tool in just any old way, i.e.:

– that individuals belonging to a single household pool their resources in entirety;

– that people belonging to the same household have the same standard of living (the average standard of living is calculated by dividing the total household income by the number of household CUs). This assumption flows from the first; the standard of living is equated with well-being.

Equivalence scales give an estimate of the additional cost linked to the presence of an additional person in a household. They say nothing about the way in which resources are actually allocated within the household. This is due to the hypothesis that resources are pooled, which is questionable (see in particular Ponthieux, 2012) and which leads to attributing the household’s average standard of living to each individual member. A couple has 1.5 CU. In fact, a couple A in which the man earns 3 times the minimum wage (SMIC) and the woman 0 times the SMIC would have the same standard of living as a couple B in which both earn 1.5 times the SMIC. This method can be used to compare the average living standards of two households, but not the living standards of the individuals who compose them. The woman in couple B probably has an individual standard of living that is higher than the woman in couple A, due to her greater bargaining power given the equal wages earned. So comparing the average living standards of the couple with the living standards of the individuals when the couple separates is misleading.

Likewise, to assess the financial burden represented by the children for the separated mother, for example, the authors apply the CU ratio linked with the children out of the total household CUs to the woman’s disposable income (salary minus the taxes paid, plus the benefits received and the support payment by her ex-partner for the two children in her care). But there is nothing to say that the separated mother does not allocate more resources to the children than is estimated by the CU ratio (with regard to housing, for example, she might sleep in the living room so that the kids each have their own room).

The methodological criticisms made of equivalence scales limit their use (see Martin and Périvier, 2015). They are not suitable for comparing the living standards of individuals, but only the living standards of households of different sizes.

What about the child’s standard of living?

There is not much literature estimating the standard of living of separated parents. To fix CUs per child in accordance with the marital status of their parents (in couples or separated), the authors rely on an Australian study that leads them to increase the CU attributed to children once the parents are separated. The cost of a child of separated parents is higher than that of a child living with both parents. They opt for the following formula:

– a child living with both parents corresponds to a CU of 0.3;

– a child living with the mother in conventional custodial care is 0.42 CU and 0.12 for the non-custodial father, i.e. 0.54 total CU for the two households.

Thus the cost of a child of a separated parent is 80% higher than that of a child living with both parents. It is likely that most separated parents do their best to keep the lives of their children unchanged after a separation. An approach that seeks to maintain the child’s standard of living makes it possible to take this into account. By increasing the cost of children by 80% when they live with both parents, and redistributing this in proportion to the CUs allocated for the children of separated parents, the custodial parent has a greater loss in living standard than that of the non-custodial parent (see the Table). This method is also questionable because it applies the additional CUs of children of separated parents over children living in couples to the monetary cost calculated in the case of a couple raising the children. But if this approach is chosen, then the result is reversed.

Any statistical analysis is based on assumptions used to “qualify” what we want to “quantify”, which is inevitable (either because we do not have the information, or for reasons of simplification and to facilitate interpretation). Assumptions that are too strong, results that are too sensitive, and perfectible methodologies are the daily lot of researchers. Providing insights, asking good questions, opening up new perspectives, feeding and feeding off of contradictions – this is their contribution to society.

The study published by France Strategy has the merit of initiating a debate on a complex subject that is challenging for our tax-benefit system. But the answers that it gives are not convincing. While the authors acknowledge that, “The interest of these simulations is above all illustrative,” they nevertheless also want that “at least they provide judges and parents with a tool to simulate the financial position of two households that have resulted from a separation by integrating the impact of the tax-benefit system”. This seems premature in view of the fragility of the results presented.

[1] To compare the standard of living of households of different sizes, equivalence scales are estimated from surveys and using a variety of methods. They are used to refer to an “adult equivalent” standard of living, or a “consumer unit” (CU). From this perspective, the standard of living of a household depends on its total income, but also on its size (number and age of its members).

[2] While Figure 7 of the working document summarizes the situations by the number of children, in the note the focus is on the case with two children.