By Catherine Mathieu and Henri Sterdyniak

The United Kingdom will leave the European Union on 29 March 2019 at midnight, two years after the UK government officially announced its wish to leave the EU. Negotiations with the EU-27 officially started in April 2017.

On 8 December 2017, the negotiators for the European Commission and the British government signed a joint report on the three points of the withdrawal agreement that the Commission considered to be a priority[1]: the rights of citizens, a financial settlement for the separation, and the absence of a border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. The European Council meeting of 14-15 December had accepted the British request for a transitional period, with the end set for 31 December 2020 (so as to coincide with the end of the programming of the current European budget). Thus, from March 2019 to the end of 2020, the United Kingdom will have to respect all the obligations of the single market (including the four freedoms and the competence of the European Court of Justice – CJEU), while no longer having a voice in Brussels. This agreement opened the second phase of negotiations.

These negotiations culminated on 14 November 2018 in a withdrawal agreement[2] (nearly 600 pages) and a political declaration on future relations between the EU-27 and the United Kingdom, which was finalized on 22 November 22 [3] ( 36 pages). The two texts were approved on 25 November at a special meeting of the European Council [4] (all 27 attending), which adopted three declarations on that occasion[5]. The withdrawal agreement and the political declaration must now be subject to the agreement of the European Parliament, which should not be a problem and, what is much more difficult, the British Parliament.

The withdrawal agreement corresponds to Article 50 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). It is a precise international agreement, which has legal value; it must be enforced by the UK courts, under the authority of the CJEU as far as EU laws are concerned. It takes up the points already settled by the negotiations in December 2017: the rights of British citizens in EU countries and the rights of EU citizens in the UK; and the financial settlement. It has three protocols concerning Ireland, Cyprus and Gibraltar. Any disagreements on the interpretation of the agreement will be managed by a joint committee and, if necessary, by an arbitration tribunal. The latter will have to consult the CJEU if this involves a question that one of the parties considers to be relevant to EU law. In July 2020, a decision could be reached to extend the transition period beyond 31 December 2020: this would require a financial contribution from the UK.

A safeguard clause will be applied to avoid the re-establishment of a physical border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland (the “backstop”): the United Kingdom will remain a member of the Customs Union if no other agreement has been concluded before the end of the transition period, and for an indefinite period, until such an agreement is reached. This agreement must be approved by the joint committee. The Customs Union will cover all goods except fisheries (and aquaculture) products. The United Kingdom will not have the right to apply a trade policy that differs from that of the Union. British products will enter the single market freely, but the UK will align with EU rules on state aid, competition, labour law, social protection, the environment, climate change and taxation. In addition, Northern Ireland will continue to align with single market rules on VAT, excise duties, health rules, etc. Controls could be put in place on products entering Northern Ireland from the rest of the United Kingdom (in particular for agricultural products), but these controls would be carried out by the UK authorities.

Thus, trapped by the issue of the Irish border, the United Kingdom must forgo for an indefinite period any independent trade policy. It will have to align itself with European regulations in many areas, subject to the threat of recourse to the CJEU.

The 22 November Joint Political Declaration outlines the possible future relations between the UK and the EU-27. On the one hand, it clearly corresponds to the goal of the close, specific and balanced relationship that the British have demanded. On the other hand, the UK is making a number of commitments that rule out any possible strategy of being a “tax and regulatory haven”.

Article 2, for instance, states that the two parties intend to maintain high standards for the protection of worker and consumer rights and the environment. Article 4 affirms respect for the integrity of the single market and the four freedoms for the EU-27, and for the United Kingdom the right to conduct an independent trade policy and to put an end to the free movement of persons.

In general, the Declaration states that both parties will seek to cooperate, to discuss, and to take concerted action; that the United Kingdom will be able to participate in Union programmes in the fields of culture, education, science, innovation, space, defense, etc., under conditions to be negotiated.

Article 17 announces the establishment of an ambitious, wide-ranging, comprehensive and balanced free trade agreement. Articles 20 to 28 proclaim the desire to create a free trade area for goods, through in-depth cooperation on customs and regulatory matters and provisions that will put all participants on an equal footing for open and fair competition. Customs duties (as well as border checks on rules on origin) will be avoided. The United Kingdom will strive to align with European rules in the relevant areas[6]. This kind of cooperation on technical and health standards will allow British products to enter the single market freely. In this context, the Declaration recalls the intention of the EU-27 and the UK to replace the Irish backstop with another device that ensures the integrity of the single market and the absence of a physical border in Ireland.

In terms of services and investment, the two parties are considering broad and ambitious trade liberalization agreements. Regulatory autonomy will be maintained, but this must be “transparent, efficient, compatible to the extent possible”. Cooperation and mutual recognition agreements will be signed on services, in particular telecommunications, transport, business services and internet commerce. The free movement of capital and payments will be guaranteed. In financial matters, equivalence agreements will be negotiated; cooperation will be established in the domain of regulation and supervision. Intellectual property rights will be protected, in particular as regards protected geographical indications. Agreements will be signed on air, sea, and land transport and on energy and public procurement. The parties pledge to cooperate in the fight against climate change and on sustainable development, financial stability, and the fight against trade protectionism. Travel for tourism or scientific, educational or business motives will not be affected. An agreement on fisheries must be signed before 1 July 2020.

Provisions will have to cover state aid and standards on competition, labour law, social protection, the environment, climate change and taxation in order to ensure open and fair competition on a level playing field.

The text provides for coordination bodies at the technical, ministerial and parliamentary levels. Every six months, a high-level conference will review the agreement.

Negotiations will continue on trade so as to ensure compatibility between the integrity of the single market and the Customs Union and the UK’s development of an independent trade policy.

On the one hand, the text provides for a close and special partnership, as requested by the United Kingdom; on the other hand, the UK pays for this by its commitment to respect European rules; finally, problematic issues still need to be negotiated, including fishing rights, an independent British trade policy, and avoiding the Irish backstop. On 25 November, the European Council wanted to adopt two declarations. The first emphasizes the importance of reaching an agreement on fisheries before the end of the transitional period and making it possible to maintain the access of EU-27 fishermen to British maritime waters. It also links the extension of the transitional period to compliance by the United Kingdom with its obligations under the Irish protocol. It recalls the conditions that the EU-27 had set on 20 March 2018 for an agreement: “The divergence in external tariffs and internal rules, as well as the absence of common institutions and a common legal system, require checks and balances and controls to safeguard the integrity of the EU single market and the UK market. Unfortunately, this will have negative economic consequences, particularly in the United Kingdom … A free trade agreement cannot offer the same advantages as the status of a Member State.” The second Declaration states that Gibraltar will not be included in the future trade agreement negotiated between the UK and the EU-27; a separate agreement will be necessary and subject to Spain’s prior approval. These declarations will not make it easy for Theresa May to win the approval of the UK Parliament.

It is necessary to highlight two points that were barely mentioned in the negotiations. This privileged partnership could serve as a model for relations with other countries. The EU has signed many customs union agreements with its neighbors, the countries of the European Economic Area (Norway, Iceland, Lichtenstein), as well as Switzerland, Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova. Five countries are candidates for entry (Albania, Montenegro, Serbia, Kosovo and Northern Macedonia). Perhaps these partnerships could be formalized in a third circle around the EU?

Does not the commitment to fair competition impose some level of tax harmonization in the EU-27, particularly with respect to the rates and terms of corporation tax? Was the EU-27 right to support the Irish Republic without some quid pro quo? It is unclear how the EU-27 could accuse the UK of practicing unfair competition when it tolerates the practices of Ireland, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. Likewise, the insistence on arrangements that prevent the UK from engaging in unfair tax and social competition contrasts with the EU’s laxity both in its relations with third countries and in the control of the internal devaluation policies of certain member countries (e.g. Germany).

On balance, the United Kingdom gets to regain its national sovereignty, to cease being subject to the CJEU, and to no longer need to respect the freedom of establishment of workers from EU countries. In return, it will have no voice in Brussels.

The business community has welcomed the proposal as it avoids the risks of No Deal and announces a free trade agreement between the UK and the EU that would impose few restrictions on trade.

To date, there is no certainty that the UK parliament will approve the deal proposed by Theresa May and the EU-27 negotiators. Theresa May must find a majority for a compromise deal. She will encounter opposition from Conservative hard Brexiteers who are prepared to leave without an agreement so that the United Kingdom can “regain control”, engage in trade negotiations with third countries, get out from under European regulations, and begin a policy of deregulation that would make the UK a tax and regulatory haven. But the UK is already one of the countries where the regulation of the goods and labor markets is the most flexible. A sharp cut in taxes would imply further cuts in social spending, contrary to the promises of the Conservative Party. And leaving with no deal would erect barriers to the UK’s access to the single market for its products and services. Theresa May will clash with the Irish Unionist Party (DUP), which is opposed to any differences in the treatment of Northern Ireland, as well as with Scottish nationalists, who want Scotland to remain in the EU. She will also have to confront the Remainers (Conservatives, Labour and Liberal Democrats) who, buoyed by some recent polls, are calling for a new referendum. While Jeremy Corbyn is not calling into question the result of the referendum, many Labour MPs could vote against the text, even if they are supporters of a soft Brexit, as the Treaty organizes. They hope to provoke early elections that could allow them to return to power. They claim they will resume negotiations after that, making every effort to obtain a better deal for the United Kingdom, which would allow it to enjoy “the same advantages as at present as members of the Customs Union and the Single Market” and to control migration. But the EU-27 has clearly refused any resumption of negotiations, and some Labour forces want a new referendum … Theresa May’s hope is that fear of a No deal will be strong enough to win approval for her compromise.

If, initially, Brexit seemed to weaken the EU, by showing that it was possible for a country leave, the EU has demonstrated its unity in the negotiations. It became clear quickly that leaving the EU was painful and expensive. The EU is a cage, more or less gilded, which it is difficult, if not impossible, to escape.

[1] See: Joint report from the negotiators of the EU and the UK government on progress during phase 1 of negotiations under Article 50 on the UK’s orderly withdrawal from the EU, 8 December 2017. See Catherine Mathieu and Henri Sterdyniak, “Brexit: Pulling off a success”, OFCE blog, 6 December 2017.

[2] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/draft_withdrawal_agreement_0.pdf

[3] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/37059/20181121-cover-political-declaration.pdf

[4] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/37114/25-special-euco-final-conclusions-fr.pdf et

[5] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/37137/25-special-euco-statement-fr.pdf

[6] The vagueness is in the text: “The United Kingdom will consider aligning with Union rules in relevant areas”.

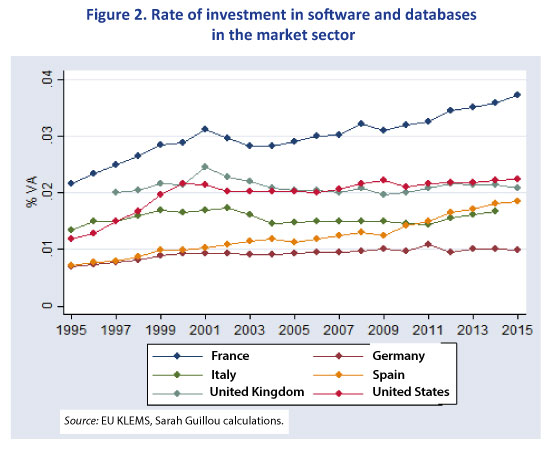

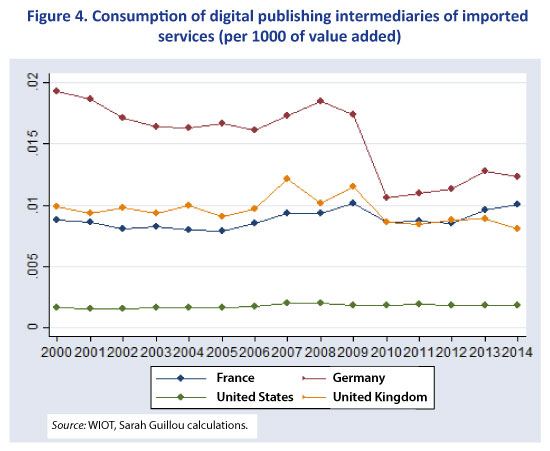

In terms of the rate of investment, that is to say, investment expenditure as a ratio of value added of the market economy, the dynamism of the French economy in terms of software and databases is confirmed: France clearly outdistances its partners.

In terms of the rate of investment, that is to say, investment expenditure as a ratio of value added of the market economy, the dynamism of the French economy in terms of software and databases is confirmed: France clearly outdistances its partners.

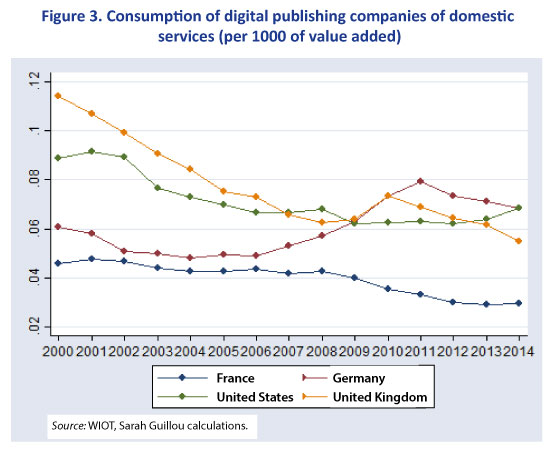

As a result, investment in software and databases would be mainly the result of in-house production, whose capital asset value (recorded as GFCF) is determined by the companies themselves. Should we conclude that GFCF is overvalued? This is a legitimate question. It calls for more specific investigation by investor and consumer sectors in order to assess the extent of overvaluation relative to economies comparable to France.

As a result, investment in software and databases would be mainly the result of in-house production, whose capital asset value (recorded as GFCF) is determined by the companies themselves. Should we conclude that GFCF is overvalued? This is a legitimate question. It calls for more specific investigation by investor and consumer sectors in order to assess the extent of overvaluation relative to economies comparable to France.

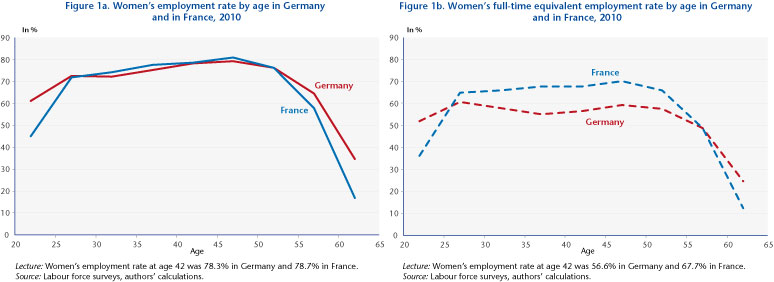

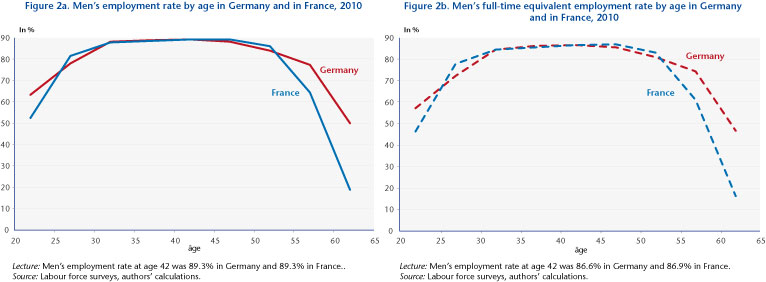

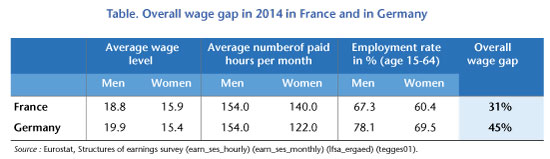

Thus policies aimed at occupational equality cannot leave aside the issue of working time and the quality of the jobs held by women. It seems that from this point of view France is doing better than Germany, although much remains to be done in this area.

Thus policies aimed at occupational equality cannot leave aside the issue of working time and the quality of the jobs held by women. It seems that from this point of view France is doing better than Germany, although much remains to be done in this area.