By Jean-Luc Gaffard

The concept of a “vertical network” [filière] is back in the spotlight and is playing the role of an instrument of the new industrial policy. A working document of the Fabrique de l’Industrie [Manufacturing Industry], ‘What use are ‘vertical networks’?” (Bidet-Mayer and Tubal, 2013) recognizes that the concept has the virtue of helping to identify good practices and develop their application in relationships between businesses and between business and government. However, the same paper concludes by questioning the merits of a concept that emphasizes an approach to industrial organization that is more technical than entrepreneurial.

Our purpose here is to explore this issue and to challenge the relevance of the “vertical network” concept and to advocate instead the notion of a “cluster”, which seems to correspond better to the need – for industrial policy – to recognize the leading role of the company in making strategic decisions.

The “vertical network”: a simplistic notion

In its old but strict sense, a “vertical network” consists of all or part of the successive stages of production, ranging from raw materials to the final product. This chain of products extends from upstream to downstream and is composed of technical relationships, which are identifiable based on technical coefficients of production. These are subsets of input-output tables that are characterized by the existence of a high level of spill-over or dominance effects that stem from the fact that the concentration of relationships is denser in some industries than in others (Mougeot, Auray and Duru, 1977).

Defined like this, a “vertical network” obviously says nothing about industrial organization per se, that is to say, about how firms set the boundaries for their activities. The companies concerned may choose to integrate the different stages in a vertical network or on the contrary focus on one stage and build pure market relations both upstream and downstream. They can also choose to form a relationship that could be described as a hybrid, based on medium-term contractual relationships both upstream and downstream.

The organizational decision takes place in a specific technical context, based on a comparison between the costs of operating through the market, through contracts or through internal transactions (Coase, 1937; Williamson, 1975). The technical features are covered over by the transaction costs and have limited relevance. The specific characteristics of the assets, which have a technical dimension, are taken into account in making the choice, but primarily because of the possibility for opportunistic behaviour (hostage-taking) that it permits.

The designation of a thusly defined “vertical network” as a tool of industrial policy, based on a certain stability of technical relations, creates an obstacle to innovation, whose major characteristic is to upset linkages within the vertical network and thus its very structure. In fact, the use of the “vertical network” concept really holds interest only for a short-term perspective, when it comes to measuring the impact of the transmission of cyclical fluctuations within a technically stable, productive structure (Mougeot, Auray and Duru, 1977).

The industrial policy measures that flow from this may affect how companies define the scope of their activities by affecting transaction costs. One example is the rules governing the relationships between contractors and subcontractors. But their effects are somewhat unclear with respect to the expected impact on the innovative capacity of the firms concerned.

The simplicity of the concept of a vertical network, together with its limitations, make the way that the concept is used (1) dangerous, if the fixed nature of the technique is taken literally (as has been the case in the past), and (2) ambiguous, if it is understood as dealing with the technical and organizational changes inherent in a market economy. As evidence of this ambiguity, consider a list of “vertical networks” today, which refer to objects such as cars, trains and planes; to luxury items whose most common feature is that they are aimed at a very rich clientele; to generic technologies such as information and communication technology; and to social issues such as health care and the ecological transition, not to mention the mishmash constituted by the consumer goods industry.

While the notion of a vertical network, that is to say, a group of industries that are technically related, has to some extent fallen into disuse since the 1980s, it is precisely because strategic business decisions are far from being dominated by technology, and a frozen state of technology in particular. The structuring of the industrial fabric is constantly changing as a result of the choices and constraints that determine them. In other words, industries are more the result of processes of innovation than of technical frameworks that supposedly control strategic choices.

It is not surprising, then, that industrial policy in the narrow sense of direct aid to companies in specific sectors has itself fallen into disuse and made room for policies on competition and regulation that are designed as efforts to move closer to a state of full competition.

The company: the essential reference

This observation does not mean that intra- and inter-vertical network relations do not matter and that all that counts are market incentives. Companies are not islands of planned coordination in a sea of ??market relations. They come to agreements about technology, distribution and marketing and develop subcontracting relationships and create joint ventures (Richardson, 1972). There is a major reason for this. To invest, a company has a need for coordination that cannot be met simply by the competitive market, but rather involves the emergence of forms of cooperation that reflect membership in a particular group. This company is characterized by its mobility, which leads it to introduce new products or even to change vertical network, thereby upsetting the relationships it has formed with others, but always along a trajectory that is determined by its core competencies.

Generally speaking, companies interact and have to solve difficulties in coordination arising from a lack of information. This is not so much a lack of technical information as a lack of information about market conditions, meaning the configuration of demand but also of competing and complementary suppliers (Richardson, 1960).

In fact, companies face two deadlines: a deadline for the gestation of irreversible investments, including investments in intangibles, and a deadline for acquiring market information. To deal with this and decide how to invest effectively, companies need to have a certain degree of confidence about the levels of competing investments and of complementary investments. The coordination required is not assured solely by market signals or, more precisely, by price signals alone. This also demands that cooperative relationships between companies complement their competitive relations (Richardson, 1960). These relationships constitute business networks for which the qualification of a “vertical network” is undoubtedly too narrow, even if technical proximities or complementarities do play a role. Belonging to a group characterized by having broadly similar skills or qualifications, rather than to a vertical network or business sector, is related to these relationships which secure the investments of each group member.

Companies seeking to innovate do not mainly face the existence of entry barriers (due to the price or investment behaviour of the established companies) or barriers to business creation. They have to deal in particular with the existence of barriers to growth that are related to their ability to be mobile (Caves and Porter, 1977). It is obviously difficult for companies to enter new business fields or to increase their size significantly. They are successful in attaining new size thresholds whenever they can acquire new managerial capabilities and ensure control of their capital. They enter into a new activity, possibly one that is quite different from their current activity in terms of the markets served, only so long as the technical and managerial skills in one business are useful in the other. Thus business groups come into being that are organized around similar or complementary skills, which transcend divisions into industries or sectors. These groups are the arenas where competition is carried out. Their very nature limits, or even thwarts, the development of an oligopolistic consensus. Because of their structural similarities, each group member responds in the same way to internal and external disturbances and anticipates the reactions of the others with a good deal of accuracy (Caves and Porter, 1977). A sort of coordination and mutual dependence thus develops within each group.

Based on this dual observation of the need for both coordination and mobility, it is clear that an industrial fabric is complex and can only with difficulty be reduced to “vertical networks” in the original meaning. Industrial policy is thereby inevitably affected, as it cannot be reduced to direct aid to firms, sectors or even technologies, nor to the application of rules on supposedly perfect competition.

Clusters: a suitable response

The nature of the productive system requires a horizontal industrial policy, which involves in particular subsidizing R&D and occupational training, but which makes sense only if this type of aid is conditional on the achievement of the objective of business mobility and of vertical as well as horizontal cooperation between companies.

It is with regard to this objective that the creation and development of clusters should be preferred, this being understood to mean groups or networks of companies and institutional structures that, while certainly having a geographical dimension, cannot necessarily be reduced to a strictly defined territory. A cluster is primarily a tool that aims to develop both voluntary cooperation between companies and a network of expertise. Its configuration is determined by the companies. The capacity building that arises from this organizational network nourishes a capillary type of action and the progressive entry of the individual members into new fields of activity.

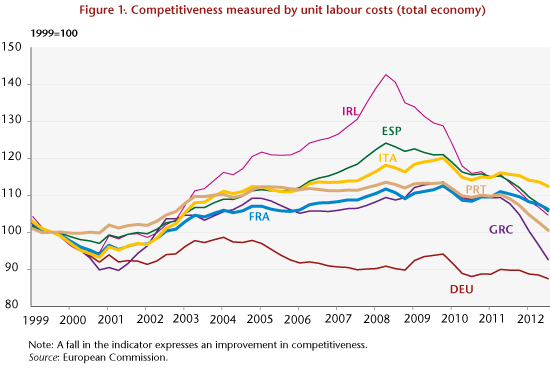

Logically speaking, the initiative for these clusters should come from the companies themselves, with the government’s role being to encourage them, specifically by making its aid contingent on the reality of the cooperation achieved. Ensuring that there is genuine cooperation requires that public funding be conditional on the contribution of private funds. The method of governance must recognize the pre-eminent role of the firms in the industry. It is this feature that has underpinned the success of German industry – it is, to say the least, risky to chalk this success up to competitiveness gains generated by labour market reform (Duval, 2013).

In this light, there should be nothing surprising about the successes and failures of industrial policy. When these configurations have the characteristics of clusters in the sense used here, whether this involves aerospace, automotive or railway, the mechanisms implemented have allowed for credible projects that have promoted competitiveness. When the supposed industries are loosely or not at all structured and bear no relationship to clusters, the failures are obvious, because there are no eligible projects under existing public procedures and in particular because of the weak involvement of small and medium-sized enterprises in collaborative projects.

The fact that the vertical networks adopted cover almost every industry forbids, moreover, any real discrimination between the forms of industrial organization. There is thus a very real risk that public funds will be wasted. Some groups, who are accustomed to dealing with the government, will capture aid for projects that they would have carried out anyway, while at the same time companies that are engaged in innovative activities will not win any support, due to failing to fit the pre-defined framework.

Once again on the question of company size

There is a functional relationship between organizational efficiency and the growth rate, with the first falling when the second rises beyond a certain threshold (Richardson, 1964). The exploitation of new investment opportunities normally goes to companies that have the most suitable production experience, business contacts and marketing skills. These capabilities are a matter of degree. The degree of organizational constraint will depend not only on the growth rate but also on the direction in which the expansion takes place. This will also depend on the extent to which the company concerned can acquire the skills, including managerial, required to be mobile without incurring excessive costs (Richardson, 1964). A cluster type organization will be able to help.

The cluster is a place for exchanges and skills transfers that facilitate the entry of firms into new fields of activity, even if only geographical, which should enable the smaller ones to grow in size. The cluster organization can also promote mechanisms that facilitate the access by small firms to the financing required for investment, while at the same time allowing them to retain control of their capital, and thus their identity.

By way of a conclusion

As is clear, industrial policy should not amount to planning based on a purely technical approach to industrial organization, the kind captured in the “vertical network” concept, which would make it hostage to local and national lobbies. Nor should it be reduced to regulatory and competition policies designed for a virtual world where the only relations among companies are market relations. It must be understood as a way to stimulate the creation and development of clusters designed as operational networks of expertise, whose governance must be ensured under conditions that favour entrepreneurial decisions, and not bureaucratic ones.

Bibliography

Bidet-Mayer, T. and L. Toubal (2013): “A quoi servent les filières?” [What’s the use of “industries”], Working document, La Fabrique de l’Industrie.

http://www.la-fabrique.fr/Chantier/a-quoi-servent-les-filieres-document-de-travail

Duval, G. (2013): Made in Germany: le modèle allemand au delà du mythe, Paris: Le Seuil.

Mougeot M., Auray J.-P. and G. Duru (1977): La structure productive française, Paris: Economica.

Richardson, G.B. (1960): Information and Investment, Oxford: Clarendon Press (Reed. 1990).

Williamson, 0. (1975): Markets and Hierarchies, Analysis and Anti-Trust Implications, New York: Free Press.