The 2014-2015 edition of The Global Competitiveness Report [1] by the World Economic Forum sheds light on the political debate between those who like to prioritize a supply policy and those who instead make the conditions governing offer their top priority. Note that competitiveness is a key factor in future growth in mature economies that specialize in high-tech or high added-value products [2].

France ranks 23rd in terms of the global competitiveness indicator calculated by the World Economic Forum. This competitiveness indicator goes beyond conventional measures based on relative production costs to incorporate many sub-indicators (100 in total) that cover a variety of dimensions, including the functioning of product markets, labour markets, and institutions; indicators about human capital, infrastructure and innovation; and qualitative measurements from business surveys. The result is a set of dimensions that identifies a country’s level of productivity in detail. The competitiveness indicator proposed is “global” in terms of both the extent of the dimensions included and the number of countries covered.

Competitiveness is measured relative to 143 countries. The weighting of the sub-indicators is deduced from the membership of countries in a category based on their level of economic development: Phase 1, governed by the availability of factors; Phase 2, in transition from Phase 1 to Phase 3; Phase 3, governed by the efficiency of the factors; Phase 4, in transition from Phase 3 to Phase 5; and Phase 5, governed by innovation. Depending on the category, the weight assigned to each sub-indicator in determining the level of competitiveness differs. This explains why the ranking does not fully reflect the traditional hierarchy of countries based on their level of economic wealth. Moreover, the diversity of the indicators that come into play can result in countries with very different economic profiles being ranked more closely: hence Russia (53rd) is nipping at the heels of Italy (49th), and the UAE comes right after Norway (11th).

With respect to the debate on supply-and-demand dynamics, it is interesting to note that the global competitiveness indicator is based on a set of sub-indicators that are not all associated with structural reforms associated with supply, and many of them result from a balanced support for demand. For example, the provision of high-quality human capital (skilled, healthy, etc.) requires not only an environment that values labour and rewards merit but also a level of security and social welfare which contributes to a quality of life that attracts and retains human capital, and therefore a certain level of public spending. This is also the case for infrastructure. More generally, the competitiveness indicator is the result of achieving a balance between the level of public spending and structural reforms in such a way that the indicators wind up complementing each other.

Switzerland’s no. 1 ranking recognizes the quality of its business environment – infrastructure, human capital, institutions, trust, macroeconomic stability – which makes up for the weakness of its market size and its degree of openness and specialization in high-tech manufacturing industries [3]. Six European countries are in the top 10, which is reassuring for the European model [4]. The French economy has stabilized its position in the ranking with respect to the previous year, following four years of decline – it was ranked 16th in 2008.

Of the 144 countries ranked, France owes its position in the first quintile (the top 20%, i.e. the first 28 countries) to the quality of its infrastructure and educational system, its technological level and its entrepreneurial culture [5]. Competitiveness is primarily a relative concept, and in a global economy where more and more countries aspire to be in the top 10 economic powers, judgments about the French economy depend heavily on the group to which it aspires to belong. What raises questions is that France long belonged to the top 10, and its main companions historically are still there (Germany, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Netherlands and the United States). Relative to the first quintile, which includes 13 other European countries, the United States, Canada, Japan and China, France’s position at the tail end is far from glorious and requires us to take a look at the indicators that rank the French economy among the least competitive. The main reasons for this result are the functioning of the labour market, the State’s fiscal position, and the country’s relatively poor performance in providing an environment favourable to work and investment.

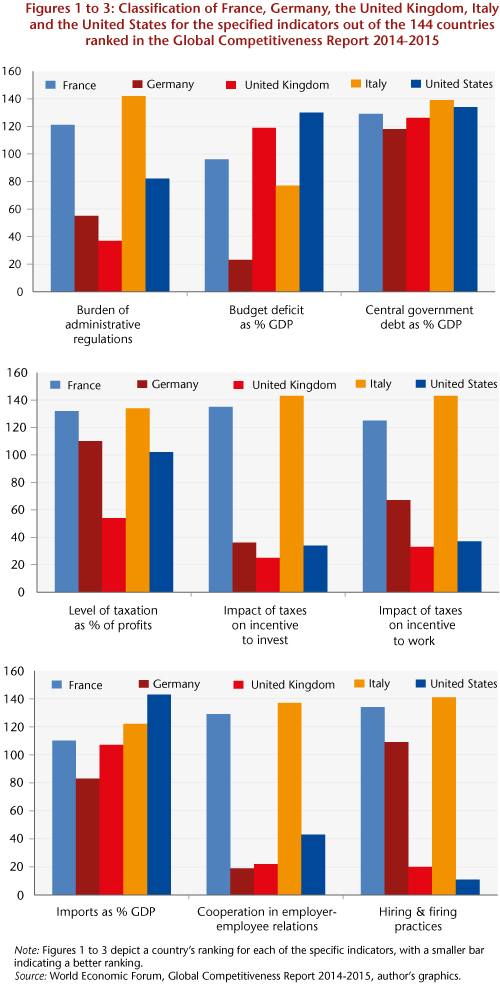

More specifically, an analysis of the specific sub-indicators (from the 100) for which France’s performance puts it in the bottom third of the 144 countries, i.e. a ranking between the 96th and 144th spots, and a comparison with its neighbours (see Figures 1-3), reveals the following points:

1) The dimensions that show the greatest contrast relative to Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States include the burden of administrative regulations, the impact of taxes on investment incentives, the impact of taxes on work incentives, cooperation in labour-management relations, hiring and firing practices and the rate of taxation as a percentage of profits.

2) France’s lacklustre performance is often exceeded by that of Italy.

3) The indicators on French fiscal policy are problematic, but this is not strongly different from the situation of its partners.

The functioning of the labour market, and more generally the regulatory environment influencing incentives to work and invest, thus emerge as the dimensions pushing down the global competitiveness indicator. Note that these indicators are derived from objective measures (such as number of regulations, level of taxation, macroeconomic data) but also in large part from responses to a survey of business leaders. These leaders have to indicate on a scale of 1 to 7 their assessment of the various factors underlying the indicators. In the main the indicators thus express a felt reality. For France, the low ranking in the dimensions identified in point 1) reveals the severity of the judgment of these business entrepreneurs.

The lessons for economic policy are as follows: the scope for progress and the specific reasons for France’s position lie in the dimensions outlined in point 1). The priorities for structural reform are cumbersome administrative regulations, incentives for work and investment, and the quality of labour-management relations. But what policies are needed to deal with these issues?

Administrative simplification and the Responsibility Pact are a step in the right direction, but it is questionable whether the measures taken will affect the way business perceives economic incentives in the administrative-legal environment. Moreover, nothing is being done in terms of improving labour-management relations. Finally, it would be desirable for government to adopt a neutral and stable position vis-à-vis companies, a position that neither maligns their economic rationality nor undermines their power over the industrial future. And even if the divorce between the State and business is in part “constitutional”, as Jean Peyrelevade [6] argues, we cannot give up efforts to improve social dialogue and to reconcile French companies with their economic and regulatory habitat. This is one of the keys to French competitiveness.

Finally, the three lessons of this Report are 1) to keep in mind that competitiveness reflects a combination of many elements that cannot simply be reduced to facilitating the exercise of economic activity (i.e. tax cuts, labour market flexibility), 2) the most competitive economies are not those where public authority has retreated, as many dimensions require a State that makes effective investments (in education and infrastructure) and guides capital (for example, into renewable energy); and 3) the margin for progress towards a more competitive France today lies not in public investment, but in incentives for social dialogue, employment, labour and investment.

The WEF classification thus provides clear evidence that supply conditions in France can be greatly improved and that to prioritize the competitiveness of the French economy reforms in this direction are imperative.

[1] The World Economic Forum began to calculate competitiveness in 1979, and since then has gradually extended its efforts to embrace more dimensions and countries.

[2] These productive activities are in effect associated with increasing returns to scale (due to high fixed entry costs, in particular R&D), which implies economic viability on a large scale: in other words, on a scale that goes beyond simply the domestic market.

[3] Likewise, political transparency is more highly valued than economic transparency.

[4] Switzerland, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Sweden.

[5] “the country’s business culture is highly professional and sophisticated” (page 23).

[6] J. Peyrelevade, Histoire d’une névrose, la France et son économie, Albin Michel, 2014.