This text is based on the 2017-2019 outlook for the global economy and the euro zone, a full version of which is available here.

The euro zone has returned to growth since mid-2013, after having experienced two crises (the financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis) that led to two recessions: in 2008-2009 and 2011-2013. According to Eurostat, growth accelerated during the third quarter of 2017 and reached 2.6% year-on-year (0.6% quarter-on-quarter), its highest level since the first quarter of 2011 (2.9%). Beyond the performance of the euro zone as a whole, the current situation is marked by the generalization of the recovery to all the euro zone countries, which was not the case in the previous phase of recovery in 2010-2011. Fears about the sustainability of the debt of the so-called peripheral countries were already being reflected in a sharp fall in GDP in Greece and the gradual slide into recession of Portugal, Spain and a little later Italy.

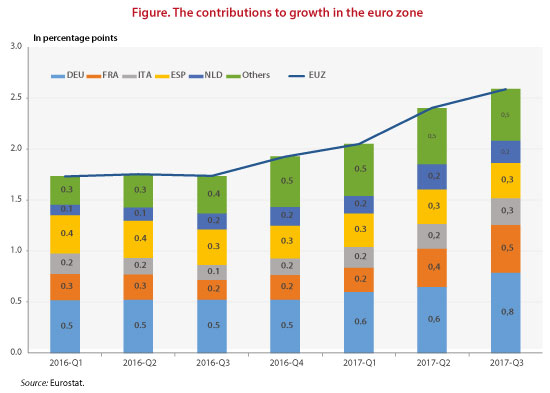

Today, while Germany remains the main engine of European growth, all of the countries are contributing to the accelerating recovery. In the third quarter of 2017, Germany’s contribution to euro zone growth was 0.8 point, a faster pace than in the previous two quarters, reflecting the vitality of the German economy (see the Figure). However, this contribution was even greater in the first quarter of 2011 (1.5 points for growth of 2.9% year-on-year). This catching-up trend is continuing in Spain, which in the third quarter of 2017 had quarterly growth of 3.1% year-on-year (0.8% quarter-on-quarter), making a 0.3 point contribution to the euro zone’s overall growth. Above all, activity is accelerating in the countries that up to now had been left a little bit out of the recovery, particularly in France and Italy, which contributed respectively 0.5 and 0.3 points to the growth of the zone over the third quarter[1]. Finally, the recovery is taking root in Portugal and Greece.

This renewed dynamism of the European economy is due to several factors. Monetary policy is still very expansionary, and the securities purchases being carried out by the Eurosystem help to keep interest rates low. Credit conditions are favourable for investment, and the access to credit for SMEs is being loosened up, especially in the countries that were hit hardest by the crisis. Finally, fiscal policy is generally neutral or even slightly expansionary.

The current optimism must not nevertheless hide the scars left by the crisis. The euro zone unemployment rate is still higher than its pre-crisis level: 9% against 7.3% at the end of 2007. The level still exceeds 10% of the active population in Italy, 15% in Spain and 20% in Greece. The social consequences of the crisis are therefore still very visible. These conditions justify the need to continue to support growth, particularly in these countries.

Leave a Reply