On 1 January 2014, Latvia will become the 18th member of the euro zone, two years after its Estonian neighbour. From a European perspective, Latvia’s entry into the “euro club” may seem of merely incidental importance. The country accounts for only 0.2% of euro zone GDP, and its integration is above all politically symbolic – it represents the culmination of the fiscal and monetary efforts undertaken by the country, which was hit hard by the crisis in 2008-2009 that slashed its GDP by almost a fifth.

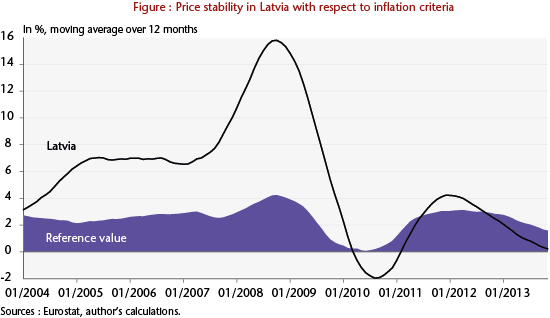

At the end of 2008, facing an emergency situation, the country requested international assistance from the IMF and the European Union, which granted this in return for a drastic austerity plan. The aid came to some 7.5 billion euros, about one-third of the country’s GDP. The national debt thus rose sharply between 2007 and 2012, from 9% of GDP to 40%. Latvia undertook a fiscal purge in order to boost its competitiveness and reduce its public deficit by drastically lowering public spending, wages and pension payments. This internal devaluation strategy led to sharp disinflation, which allowed Latvia to meet the ERM II goal for price stability (see chart). In accordance with IMF advice, the country has stuck to its goal of joining the euro zone quickly while categorically refusing to use the weapon of an external devaluation to get out of the crisis. It has for instance adhered to its policy of maintaining a fixed exchange rate against the euro without interruption since 1 January 2005.

2011 saw the country’s return to growth, which was driven mainly by external demand from the Nordic countries and Russia. As for the public deficit, it rose from 9.8% of GDP in 2009 to 1.3% in 2012. Sovereign bond rates have fallen, which enabled the country to borrow only 4.4 billion euros (instead of the 7.5 billion planned) and to repay its debt to the IMF (three years in advance). Public debt has stabilized at around 40%. In addition, Latvia has met its inflation target over the reference period used to decide the issue of its euro zone membership. These various factors led the European Union to give it the green light in June 2013.

So is the entry of Latvia of merely incidental importance? Not entirely. First, Latvia has still not erased the scars of the crisis; in 2012, GDP was below its 2007 level in real terms. Furthermore, while the unemployment rate has been cut almost in half since 2009, it still represents 11.9% of the workforce, and most importantly, this reduction has been due in part to high emigration. But above all, as was pointed out by the European Central Bank in its Convergence Report, nearly one-third of bank deposits (a total of 7 billion euros) are held by non-residents, particularly from Russia. As with Cyprus, this poses a high risk to banking stability in a crisis situation, with the potential for capital flight. At a time when the proposed banking union is stumbling up against the heterogeneity of the euro zone’s banking systems, this illustrates yet again that it is very difficult to reconcile the logic of economic integration with the political choice of enlargement. Whether at the level of the euro zone or at the level of the European Union, it is time for Europe to make a clear choice between these two opposing logics.