By Christophe Blot and Jérôme Creel

The debate on economic policy in Europe was re-ignited this summer by Mario Draghi during the now traditional symposium at Jackson Hole, which brings together the world’s main central bankers. Despite this, it seems that both the one side (Wolfgang Schaüble, Germany’s finance minister) and the other (Christine Lagarde, head of the IMF) are holding to their positions: fiscal discipline plus structural reforms, or demand stimulus plus structural reforms. Although the difference can seem tenuous, the way is now open for what Ms. Lagarde called “fiscal manoeuvring room to support a European recovery”. She is targeting Germany in particular, but is she really right?

In an interview with the newspaper Les Echos, Christine Lagarde said that Germany “very likely has the fiscal manoeuvring room necessary to support a recovery in Europe”. It is clear that the euro zone continues to need growth (in second quarter 2014, GDP was still 2.4% below its pre-crisis level in first quarter 2008). Despite the interest rate cuts decided by the ECB and its ongoing programme of exceptional measures, a lack of short-term demand is still holding back the engine of European growth, mainly due to the generally tight fiscal policy being pursued across the euro zone. In today’s context, support for growth through more expansionary fiscal policy is being constrained by tight budgets and by a political determination to continue to cut deficits. Fiscal constraints may be real for countries that are heavily in debt and have lost market access, such as Greece, but they are more of an institutional nature for countries able to issue government debt at historically very low levels, such as France. For Ms. Lagarde, Germany has the manoeuvring room that makes it the only potential economic engine for powering a European recovery. A more detailed analysis of the effects of its fiscal policy – both internally and spillovers to European partners – nevertheless calls for tempering this optimism.

The mechanisms that underlie the hypothesis of Germany driving growth are fairly simple. An expansionary fiscal policy in Germany would boost the country’s domestic demand, which would increase imports and create additional opportunities for companies in other countries in the euro zone. In return, however, the impact could be tempered by a slightly less expansionary monetary policy: as Martin Wolf argues, didn’t Mario Draghi ensure that the ECB would do everything in its power to ensure price stability over the medium term?

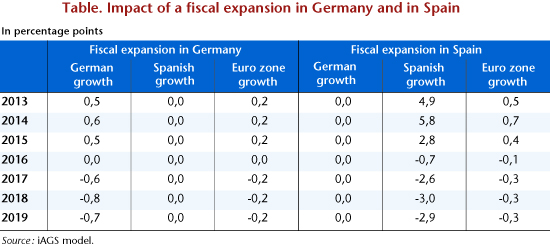

In a recent OFCE working document, we have tried to capture these various commercial and monetary policy effects in a dynamic model of the euro zone. The result is that a positive fiscal impulse of 1 GDP point in Germany for three consecutive years (a plan involving 27.5 billion euros per year [1]) would boost growth in the euro zone by 0.2 point in the first year. This impact is certainly not negligible. However, this is due solely to the stimulation that would benefit German growth and not to spillovers to Germany’s European partners. Indeed, and as an example, the increase in Spain’s growth would be insignificant (0.03 point of growth in the first year). The weakness of the spillover effects can be explained simply by the moderate value of Germany’s fiscal multiplier [2]. Indeed, the recent literature on multipliers suggests that they rise as the economy goes deeper into a slump. But based on the estimates of the output gap retained in our model, Germany is not in this situation, and indeed the multiplier has dropped to 0.5 according to the calibration of the multiplier effects selected for our simulations. For an increase in German growth of 0.5 percentage points, the effect of the stimulation on the rest of the euro zone is therefore low, and depends on Germany’s share of exports to Spain and the weight of Spanish exports in Spanish GDP. Ultimately, a German recovery would undoubtedly be good news for Germany, but the other euro zone countries may be disappointed, just as they undoubtedly will be from the implementation of the minimum wage, at least in the short term, as is suggested by Odile Chagny and Sabine Le Bayon in a recent post. We can also assume that in the longer term the German recovery would help to raise prices in Germany, thereby degrading competitiveness and providing an additional channel through which other countries in the euro zone could benefit from stronger growth.

And what would happen if the same level of fiscal stimulus were applied not in Germany, but rather in Spain, where the output gap is more substantial? In fact, the simulation of an equivalent fiscal shock (27.5 billion euros a year for three years, or 2.6 points of Spanish GDP) in Spain would be much more beneficial for Spain but also for the euro zone. While in the case of a German stimulus, growth in the euro zone would increase by 0.2 percentage points over the first three years, it would increase by an average of 0.5 points per year for three years in the event of a stimulus implemented in Spain. These simulations suggest that if we are to boost growth in the euro zone, it would be best to do this in the countries with the largest output gap. It is more effective to spend public funds in Spain than in Germany.

In the absence of any relaxation of the fiscal constraints on Spain, a stimulus plan funded by a European loan, whose main beneficiaries would be the countries most heavily affected by the crisis, would undoubtedly be the best solution for finally putting the euro zone on a path towards a dynamic and sustainable recovery. The French and German discussions of an investment initiative are therefore welcome. Hopefully, they will lead to the adoption of an ambitious plan to boost growth in Europe.

[1] The measure is then compensated in a strictly equivalent way so that the shock amounts to a transient fiscal shock.

[2] Recall that the fiscal multiplier reflects the impact of fiscal policy on economic activity. Thus, for one GDP point of fiscal stimulus (or respectively, tightening), the level of activity increases (respectively, decreases) by k points.