By Christophe Blot, Paul Hubert and Fabien Labondance

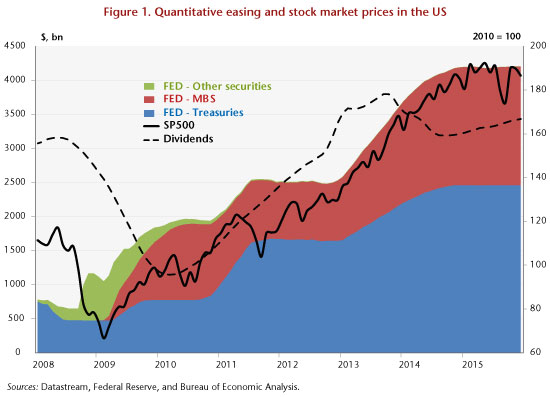

Has the implementation of unconventional monetary policies since 2008 by the central banks created new bubbles that are now threatening financial stability and global growth? This is a question that comes up regularly (see here, here, here or here). As Roger Farmer shows, it is clear that there is a strong correlation between the purchase of securities by the Federal Reserve – the US central bank – and the stock market index (S&P 500) in the United States (Figure 1). While the argument may sound convincing at first glance, the facts still need to be discussed and clarified. First, it is useful to remember that correlation is not causation. Secondly, an increase in asset prices is precisely a transmission channel for conventional monetary policy and quantitative easing (QE). Finally, an increase in asset prices cannot be treated as a bubble: developments related to fundamentals need to be distinguished from purely speculative changes.

Higher asset prices is a factor in the transmission of monetary policy

If the ultimate goal of central banks is macroeconomic stability [1], the transmission of their decisions to the target variables (inflation and growth) takes place through various channels, some of which are explicitly based on changes in asset prices. Thus, the effects expected from QE are supposed to be transmitted in particular by so-called portfolio effects. By buying securities on the markets, the central bank encourages investors to reallocate their securities portfolio to other assets. The objective is to ease broader financing conditions for all economic agents, not just those whose securities are targeted by the QE programme. In doing this, the central bank’s actions push asset prices up. It is therefore not surprising to see a rise in equity prices in connection with QE in the US.

Every increase in asset prices is not a bubble

Furthermore, it is necessary to make sure that the correlation between asset purchases and their prices is not just a statistical artefact. The increase observed in prices may also reflect favourable fundamentals and be due to improved growth prospects in the United States. The standard model for determining the price of a financial asset identifies its price as equal to the present value of anticipated income flows (dividends). Although this model is based on numerous generally restrictive assumptions, it nevertheless identifies a first candidate, changes in dividends, to explain changes in stock prices in the United States since 2008.

Figure 1 shows a clear correlation between the series of dividends [2] paid and the S&P 500 index between April 2010 and October 2013. Part of the rise in equity prices can be explained simply by the increase in dividends: the usual determinant of stock market prices. Looking at this indicator, only the period starting at the beginning of 2014 could then indicate a disconnect between dividends and share prices, and thus possibly point to an over-adjustment.

A correlation that isn’t found in the euro zone

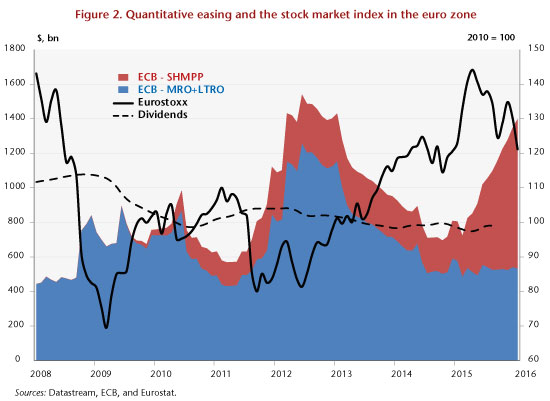

If the theory that unconventional monetary policies create bubbles is true, then it should also be observed in the euro zone. Yet performing the same graph as the one for the United States does not reveal a link between the liquidity provided by the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Eurostoxx index (Figure 2). The first phase in the increase in the size of the ECB’s balance sheet, via its refinancing operations starting in September 2008, came at a time when stock markets were collapsing, following the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. Likewise, the very long-term refinancing operations carried out by the ECB at the end of 2011 do not seem to be correlated with the stock market index. The rise in share prices coincides in fact with Mario Draghi’s statement in July 2012 that put a halt to concerns about a possible breakup of the euro zone. It is of course possible to argue that the central bank has played a role, but any link between liquidity and asset prices is simply not there. At the end of 2012, the banks paid back their loans to the ECB, which reduced the cash in circulation. Finally, the recent period is once again illustrating the fragility of the argument that QE creates bubbles. It is precisely at a time when the ECB is undertaking a programme of large-scale purchases of securities, along the lines of the Federal Reserve, that we are seeing a fall in world stock indices, in particular the Eurostoxx.

So does this mean that there is no QE-bubble link?

Not necessarily. But to answer this question, it is necessary first to identify precisely the portion of the increase that is due to fundamentals (dividends and companies’ share prospects). A bubble is usually defined as the difference between the observed price and a so-called fundamental value. In a forthcoming working paper, we endeavour to identify periods of over- or undervaluation of a number of asset prices for both the euro zone and the United States. Our approach involves estimating different models of asset prices and thereby to extract a component that is unexplained by fundamentals, which is then called a “bubble”. We then show that for the euro zone, the ECB’s monetary policy broadly speaking (conventional and unconventional) does not seem to have a significant effect on the “bubble” component (unexplained by fundamentals) of asset prices. The results are stronger for the United States, suggesting that QE might have a significant effect on the “bubble” component of some asset prices there.

This conclusion does not mean that the central banks and the regulators are impotent and ignorant in the face of this risk. Rather than trying to dissect every movement in asset prices, the central banks should focus their attention on financial vulnerabilities and on the ability of agents (financial and non-financial) to absorb sharp fluctuations in asset prices. The best prevention against financial crises thus consists of continuously monitoring the risks being taken by agents rather than trying to limit variations in asset prices.

[1] We prefer a broad definition of the end objective that takes into account the diversity of institutionalized formulations of the objectives of central banks. While the mandate of the ECB is primarily focused on price stability, the US Federal Reserve has a dual mandate.

[2] The series of dividends paid shows strong seasonality, so this has been smoothed by a moving average over 12 months.

Leave a Reply