* This text summarizes the outlook produced by the Department of Analysis and Forecasting for the euro zone economy in 2012-2013, which is available in French on the OFCE web site

The euro zone is still in crisis: an economic crisis, a social crisis and a fiscal crisis. The 0.3% decline in GDP in the fourth quarter of 2011 is a reminder that the recovery that began after the great drop of 2008-2009 is fragile and that the euro zone has taken the first step into recession, which will be confirmed in early 2012.

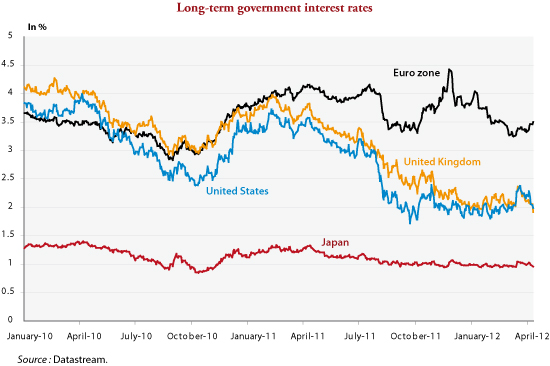

The fall in the average long-term government interest rate in the euro zone seen since the beginning of the year has come to a halt. After reaching 3.25% on 9 March, it rose again due to new pressures that emerged on Italian and Spanish rates. Indeed, despite the agreement to avoid a default by Greece, Spain was the source of new worries after the announcement that its budget deficit had reached 8.5% in 2011 – 2.5 points above the original target – and the declaration that it would not meet its commitments for 2012, which has reinforced doubts about the sustainability of its debt. The Spanish situation illustrates the close link between the macroeconomic crisis and the sovereign debt crisis that has hit the entire euro zone. The implementation of fiscal adjustment plans in Europe, whose impact is being amplified by strong economic interdependence, is causing a slowdown or even a recession in various euro zone countries. The impact of synchronized restrictions is still being underestimated, to such an extent that governments are often being assigned targets that are difficult to achieve, except by accepting an even sharper recession. So long as the euro zone continues to be locked in a strategy of synchronized austerity that condemns in advance any resumption of activity or reduction in unemployment, the pressure will not fail to mount once again in 2012. Long-term public interest rates in the euro zone will remain above those of the United States and the United Kingdom (see the figure), even though the average budget deficit was considerably lower in 2011 in the euro zone than in these two countries: 3.6% against 9.7% in the US and 8.3% in the UK.

To pull out of this recessionary spiral, the euro zone countries need to recognize that austerity is not the only way to reduce budget deficits. Growth and the level of interest rates are two other factors that are equally important for ensuring the sustainability of the public debt. It is therefore urgent to set out a different strategy, one that is less costly in terms of growth and employment, which is the only way to guarantee against the risk that the euro zone could fall apart. First, generalized austerity should be abandoned. The main problem with the euro zone is not debt but growth and unemployment. Solidarity must be strengthened to curb speculation on the debt of the weaker countries. The fiscal policies of the Member states also need to be better coordinated in order to mitigate the indirect effects of cutbacks by some on the growth of others [1]. It is necessary to stagger fiscal consolidation over time whenever the latter is needed to ensure debt sustainability. At the same time, countries with room for fiscal manoeuvre should develop more expansionary fiscal policies. Finally, the activities of the European Central Bank should be strengthened and coordinated with those of the euro zone governments. The ECB alone has the means to anchor short-term and long-term interest rates at a sufficiently low level to make it possible both to support growth and to facilitate the refinancing of budget deficits. In two exceptional refinancing operations, the ECB has provided more than 1,000 billion euros for refinancing the euro zone banks. This infusion of liquidity was essential to meet the banks’ difficulties in finding financing on the market. It also demonstrates the capacity for action by the monetary authorities. The portfolio of government debt securities held by the ECB at end March 2012 came to 214 billion euros, or 2.3% of euro zone GDP. In comparison, in the United States and the United Kingdom, the portfolio of government securities held by the central banks represents more than 10% of their GDP. The ECB therefore has significant room for manoeuvre to reduce the risk premium on euro zone interest rates by buying government securities in the secondary markets. Such measures would make it possible to lower the cost of ensuring the sustainability of the long-term debt.

____________________

[1] See “He who sows austerity reaps recession”, OFCE note no. 16, March 2012.